Right next door to the In and Out Club and on the corner of Half Moon Street is another large property which is in a surprising state of semi-dereliction with creepers growing out of the first floor. It’s 90-93 Piccadilly, designed by J.G.F.Noyes in 1883:-

Monthly Archives: December 2014

In and Out Club

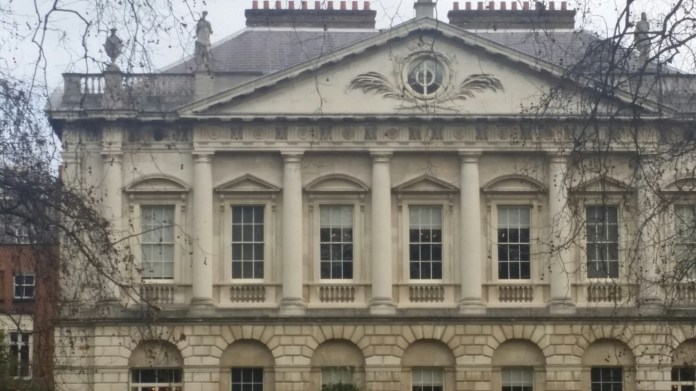

Every so often I go past the old In and Out Club to check that it’s still unrestored. It’s on the north side of Piccadilly, just west of Half Moon Street. It was built in 1756 by Matthew Brettingham for Charles Wyndham, second Earl of Egremont, a smart and smooth politician who died of over-eating in 1763 (shortly before his death he commented that he had ‘three turtle dinners to come, and if I survive them I shall be immortal’). In the 1820s, the house was owned by the Marquess of Cholmondeley and was known as Cholmondeley House and then in 1829 was taken over by the Duke of Cambridge and was known as Cambridge House. After being owned by Lord Palmerston, it was bought by the Naval and Military Club, always known as the In and Out because of the signs on the entrance gates:-

Spencer House

I had a Christmas lunch in Spencer House, always a pleasure, not least for the opportunity of seeing inside one of the best preserved of the eighteenth-century mansions in the west end. It was originally designed by John Vardy for John Spencer, first Earl Spencer. According to the terms of his inheritance from the ghastly Duchess of Marlborough, Spencer was not able to take government office, so devoted himself instead to the construction of Spencer House and the pleasures of garden parties and shooting at Althorp. At Spencer House, Vardy was replaced by James ‘Athenian’ Stuart, who decorated it in a style which is heavier and more emphatic than his rival, Robert Adam:-

Wapping (2)

The rest of my tour of the sights of Wapping included:-

Phoenix Wharf, one of the best preserved of the riverside warehouses, less poshed up and neo-Victorianised than the others. It turns out that it was designed by Sidney Smirke RA, the architect of our exhibition galleries, in 1840:-

Wapping (1)

I have been totally jinxed on a post at the weekend from Wapping. For some reason, it seems impossible to file.

Suffice it to say that I discovered, which I should have known, that it’s possible get down to the river by way of two small alleyways off Wapping High Street. The first is alongside New Crane Wharf:-

St. Mary and St. Joseph, Poplar

The last of my Poplar sights is the Catholic church of St. Mary and St. Joseph, which is said by Pevsner to be at odds with the picturesque surroundings of the Lansbury estate (‘the mannered modernistic Gothic detail is totally at odds with the character of the surroundings’). It is by Adrian Gilbert Scott, grandson of Sir Gilbert Scott, younger brother to Sir Giles Gilbert Scott and architect of the Anglican cathedral in Cairo and, to my eyes at least, is an effective marrying of Scandinavian modernist brickwork with robust French gothic massing:

Balfron Tower

I was castigated yesterday for having limited my Poplar excursion to Robin Hood Gardens and not having included the nearby Balfron Tower, Ernö Goldfinger’s monumental, if bleak, tower block which overlooks the entrance to the Blackwall Tunnel. I was told it was particularly fine in its relationship to its setting. I don’t see this. It’s not quite my style, but I can see that it’s impressive:

St. Anne’s, Limehouse

As it was such a sunny day, I called in at St. Anne’s, Limehouse to see the light on the great sculptural mass of the first of Hawksmoor’s east end churches and, at least in its exterior, one of the noblest and best preserved, like the mast of a ship as the boats came up the Thames:

Poplar

Poplar always looks and feels as if it was heavily bombed, without any relics of its seventeenth-century shipyards and consisting mainly of large 1930s and 1950s estates. At its heart is St. Matthias, which contains within its mid-Victorian ragstone casing the original chapel of the East India Company which first opened in the early 1650s:

Robin Hood Gardens

A trip to the local off licence made it possible for me to see what is happening to Robin Hood Gardens (or not), following the decision to demolish it by Margaret Hodge, supported by the Commissioners of English Heritage, in spite of it being one of the more important surviving examples of post-war housing and designed by Alison and Peter Smithson. The answer is that it is still there, with an eastern European air of neglect, but full of what look like architectural students, still with its original sculptural sweep and no more gloomy – in fact, much less so – than the rest of Poplar:

You must be logged in to post a comment.