I had arranged to visit the Science Museum yesterday.

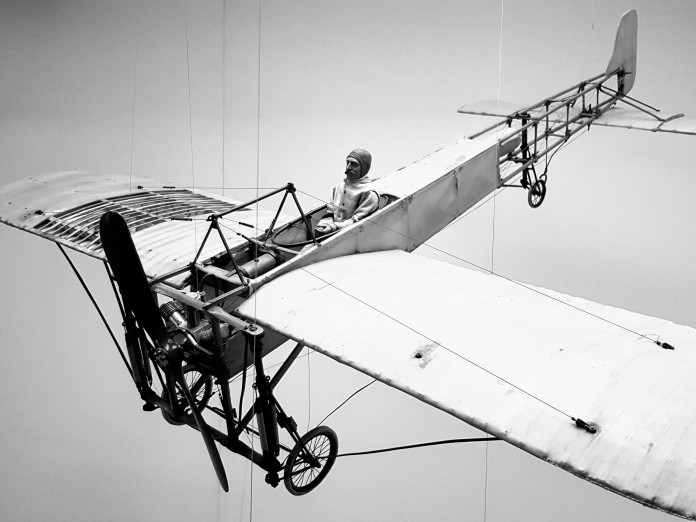

Although I worked for twelve years on the other side of the road, I realised how little I knew about the history of the Science Museum. Originally, it was the Museum of Patents, attached in a little cottage to the Brompton Boilers, when the South Kensington Museum opened in 1857, and at a time when the South Kensington Museum was much more eclectic than it has since become, including collections of Animal Products, Food, and Building Materials. Stephenson’s Rocket was put on display in 1862. The collections gradually moved across the road to the site of the 1862 International Exhibition, producing the binary divide between art and science on either side of Exhibition Road. The Science Museum was officially separated from what had become the Victoria and Albert Museum on 26 June 1909, owing to the support of Robert Morant, the former tutor to the Crown Prince of Siam, who had become an energetic and reformist Permanent Secretary in the Board of Education aged 40. Work on the new building started in 1913, but was interrupted by the First World War and only opened in 1928:-

The traditions of the Science Museum have always been rather different from those of the V&A because Sir Henry Lyons, who was Director in the 1920s was much more interested in the needs of ‘the ordinary visitor’ rather than those of the specialist and was an early advocate of interactive displays, establishing a ‘Children’s Gallery’ in 1931.

What I was interested in is how the Science Museum handles voluntary donations. One has to queue in line as if to buy a ticket, and then is asked for a donation:-

It is genuinely voluntary, much more so than its equivalent at the Metropolitan Museum, which has recently been abolished. Is it a way of ensuring higher contributions from visitors ?

You must be logged in to post a comment.