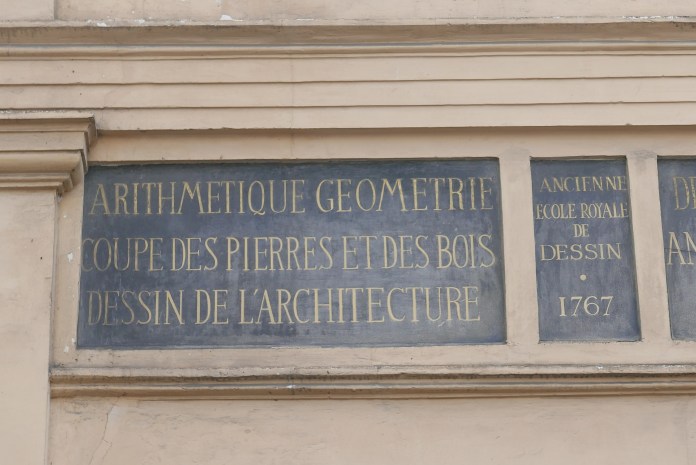

I was walking down a street near the Musée de Cluny (the Rue de l’Ecole de Médicine to be precise), I spotted an inscription recording that it was the location of the Ancienne Ecole Royale de Dessin, which was established in 1767. In all the literature about the establishment of the Royal Academy (which is itself devoted to ‘the arts of design’), I have never seen any reference to the fact that the French King had given his blessing to an official drawing school which had been established in 1766 in what was then the rue des Cordeliers by Jean-Jacques Bachelier. After various increases in its responsibilities to include the mechanical arts in 1823, it became L’École nationale des arts decoratifs’ in 1873. But it still retains a fine relief of Architecture flanking its entrance portal and inside is what I suspect is the original drawing school:-

Monthly Archives: October 2017

Left Bank

I have tended to avoid the left bank in recent years, having long ago been put off the tourist aspects of the Boulevard Saint-Germain and Les Deux Magots. But staying next to the Sciences Po meant that I have had a chance to get to know the Faubourg Saint-Germain better, with its well preserved side streets, its antiquaires, its courtyards and gardens. I liked the scientific bookshop at 48, Rue Jacob with its display of old opticians’ equipment and eyeballs:-

The doorways further down the street in the Rue Jacob and surrounding neighbourhood:-

The Square Gabriel-Pierne at the end of the Rue Mazarine:-

And the Musée Delacroix:-

Musée de Cluny

Having been a touch disappointed by the Cloisters recently, I thought I should visit the Musée de Cluny, which is the original of this form of medieval reconstruction, established in 1843 by Alexandre de Sommerard in the old, partly medieval hotel of the abbots of Cluny:-

An early sixteenth-century altarpiece:-

An early sixteenth-century altarpiece:-

The decapitated statues from Notre-Dame, which were vandalised during the Revolution and only rediscovered in the 1970s:-

The decapitated statues from Notre-Dame, which were vandalised during the Revolution and only rediscovered in the 1970s:-

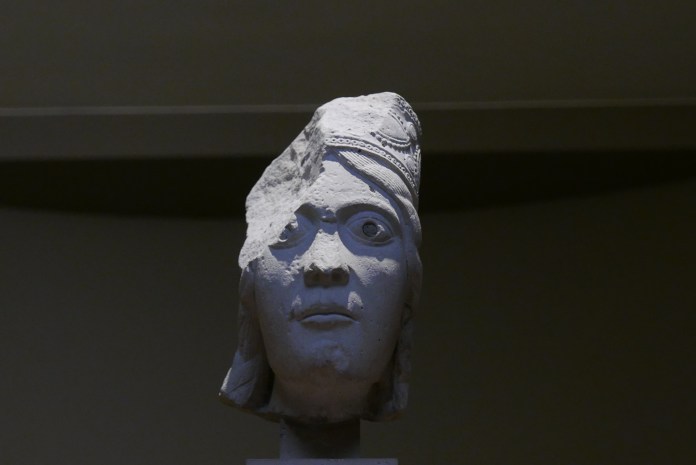

The head of the Queen of Sheba from the portal of the Abbaye de Saint-Denis:-

The head of the Queen of Sheba from the portal of the Abbaye de Saint-Denis:-

A fox from The Lady and the Unicorn tapestries:-

A seventh-century ivory:-

The head of St. Florion from the end of the fifteenth century:-

Musée d’Orsay

It’s a while since I’ve been able to see Gae Aulenti’s grand and slightly camp conversion of the Gare d’Orsay which opened in 1986 and caused consternation because of its relegation of the Impressionists into the attics and reinstatement of the French academic tradition:-

What I’d forgotten, or may not previously have seen are the decks of French nineteenth-century decorative arts on the first floor. This is a bust of the Comtesse de Béarn by Emile Gallé:-

A Virgin by Eugène Delaplanche:-

L’École des Beaux Arts

As I was walking up the Rue Bonaparte, I was stopped short by a massive head of Poussin (1838 by Michel-Louis Mercier):-

As I was trying to take a photograph, not altogether successfully, the doorman kindly let me in and I was able to wander freely through the whole site, which, once upon a time, was the Musée des Monuments Francais, laid out by Alexandre Lenoir after the French Revolution. Once the Museum closed in 1816, it was given to the École des Beaux Arts, which had originally been the Academie Royale. Their architect, Francois Debret, and his brother-in-law, Felix Duban, retained many of the older elements as a palimpsest:-

The gardens are full of odd and unexpected remains:-

From here, I found myself in the Palais des Etudes, which was glassed over in 1863:-

I’ve always thought that art schools are unexpectedly good preservers of historic buildings because they are completely without sanctimony and treat buildings roughly, but with respect:-

Maison de Verre

En route to Paris, I had luckily spotted that the Sciences Po is right next door to the Maison de Verre and that, since it was bought in 2006 by an American commodities-trader, it has generally been open on Thursday afternoon. So, at five o’clock precisely, I was granted temporary admittance to the courtyard which contains Pierre Chareau and Bernard Bijvoet’s glass facade, erected between 1928 and 1932 for Dr. Dalsace, a gynecologist, who had his offices on the ground floor. Although Dalsace was a medical practitioner, he also knew intellectuals, so I liked to imagine Walter Benjamin standing where I stood in 1934:-

Sciences Po

I have just given half of a class about cultural governance to the graduate students of the Sciences Po, the elite school of political administration (Ecole Libre des Sciences Politiques) which was established in Paris in February 1872 by a group of intellectuals, including Hippolyte Taine, in order to train candidates for the French civil and diplomatic service. What was interesting was how idiosyncratic the British system of corporate governance looks by comparison to the French which was standardised in 1982 to include one third representatives of the state, one third subject experts, and one third representatives of staff, whereas British boards are in theory constituted as independent bodies, but appointed by the Prime Minister, which is fine as long as government chooses not to interfere, but not so fine when it does.

Soane Museum

It was as ever a pleasure to be able to wander round the back regions of the Soane Museum where Soane displayed his best antiquities alongside plaster casts in layer upon layer up into the dome, presided over by Francis Chantrey’s bust of himself (as Chantrey wrote on 5 April 1829, ‘Whether the bust…shall be considered like John Soane or Julius Caesar is a point that cannot be determined by either you or me. I will, however, maintain that as a work of art I have never produced a better’):-

Soane’s Ark

I went last night to the opening of Ferdinand SS’s exhibition on John Soane’s Ark of the Masonic Covenant which is being held in the new Foyle Gallery at the back of the Soane Museum (formerly known as the NEW PICTURE-ROOM). There was the reconstruction of the Ark itself, resplendent, made by Houghtons of York and with beautifully executed detailing in the three orders at each of the corners and in the scrollwork on top:-

Sir T.G. Jackson RA

I have been swotting up on the life of Graham Jackson who was responsible for the design of the front entrance hall in Burlington House.

The child of high minded, evangelical parents, he was educated at Brighton College and Wadham, where he got a third in Greats, but a first in Natural Sciences. He then trained as an architect in the office of Giles Gilbert Scott, the prolific Victorian architect and restorer, who encouraged him ‘to bring your Pre-Raffaelitism into architecture’ and then instructed him in the fierce tenets of the Gothic Revival. Jackson set up in independent practice in 1862 and was elected to a prize fellowship at Wadham in 1864, which allowed him a long gestation as an architect before winning the competition to design the New Examination Schools on the High Street in Oxford, a large and rather gloomy building next door to University College, but with very good and serious English Renaissance detailing. He probably won the competition as a graduate of the university and Fellow of Wadham, friend of the reforming faction in the university, and went on to do an immense amount of other work for the colleges, including The New Building and President’s Lodging at Trinity, New Buildings for Corpus, also in Neo-Renaissance style, The Grove Building for Lincoln, most of Hertford, including its chapel, and the façade of Brasenose, next to the University Church, which he was controversially also responsible for repairing. He was not only a prolific architect, but also wrote widely about historic architecture, beginning with the publication of Modern Gothic Architecture in 1873, which signalled his rejection of the Gothic Revival and embrace of what he called a ‘judicious eclecticism’. More unexpectedly, he wrote ghost stories in the style of M.R. James.

Elected an Associate of the Royal Academy in January 1892, a full RA in November 1896, and Treasurer in 1901, in 1899 Jackson embarked on ambitious plans for the refurbishment of the the Academy’s front entrance hall, including laying a new marble floor to replace the old red and black encaustic floor put down in 1868 by Sydney Smirke. The minutes of Council record how ‘It was Resolved that the Entrance Hall should be repaved with black & white marble slabs after the pattern of the old pavement of Burlington House as seen in the Keeper’s House, & the Treasurer was requested to procure estimates for the same’. The proposal was subsequently approved by General Assembly and in the Annual Report for 1899, it was recorded that ‘Another great improvement which has been successfully carried out is the alteration and decoration of the Entrance Hall’. The total cost was £2,586 19s. 3d.

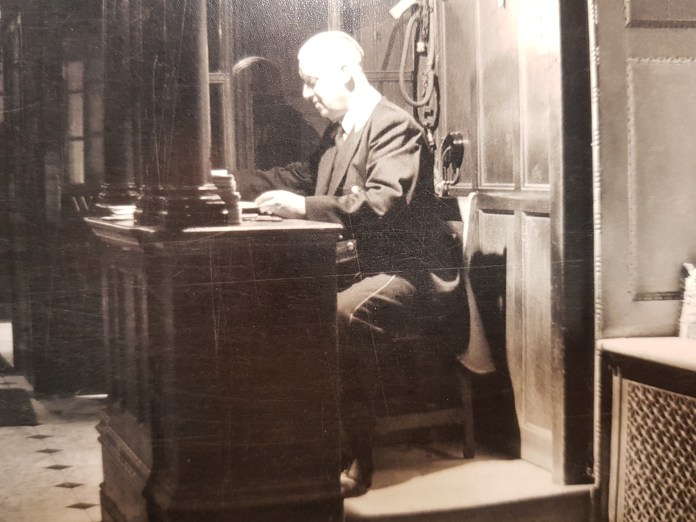

This is the new security box:-

And this is Jackson’s design for a letter box:-

You must be logged in to post a comment.