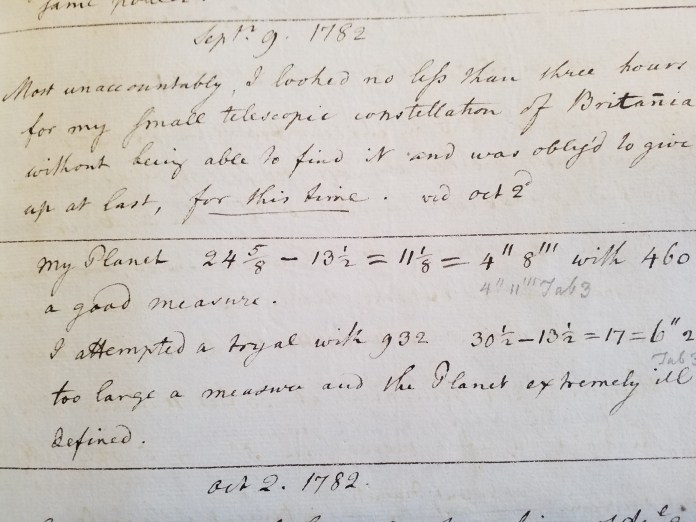

The other thing that I was really impressed by in the Royal Astronomical Society’s Library was the manuscript ‘observing book’ in which William Herschel described his observations of the planets, including the entry on 9th. September 1782 in which he sighted ‘My Planet’, which was Uranus – ‘the Planet extremely ill defined’. He is the one and only person to have discovered a new planet from his observatory which he had recently moved from Bath to Slough:-

Monthly Archives: January 2018

Spitalfields Mathematical Society

I was invited this afternoon to meet the new Executive Director of the Royal Astronomical Society, one of our neighbours in the courtyard, and to see some of the books in their library. I was most struck by the fact that they have inherited books and manuscripts from the library of the Spitalfields Mathematical Society, a group which was established in Spitalfields in 1717 by Joseph Middleton to teach maths to sailors. It met in a pub, the Monmouth’s Head, until 1725, when it moved to the White Horse in Wheeler Street. Apparently about half its members were weavers – presumably Huguenot – and the rest were a motley crew of ‘brewers, braziers, bakers, bricklayers’. The Society existed until 1845 when its membership lapsed and was absorbed into that of the Royal Astronomical Society, founded in 1820.

Toasts

I was asked on Tuesday evening at our lenders’ dinner for Charles I about the origins of the two very distinctive Royal Academy toasts – the first to Our Patron, Protector and Supporter, Her Majesty the Queen and the second, more unusually, ‘Honor and Glory to the Next Exhibition.

Of course, I didn’t know. But Mark Pomeroy, our excellent archivist, has been able to supply the answer:-

The earliest recorded list of toasts comes from Council minutes in 1785: The King, The Queen, Prince of Wales & rest of the Royal Family, The Duc de Chartres & the rest of the Noblemen & Gentlemen who have honoured us with their presence , Lord Mayor and the City of London, Sr. Jos. Banks and the Royal Society, Lord Leicester and the Antiquarian Society, Prosperity to the Royal Academy, The Council. References to Patron, Protector & Supporter and Honor & Glory in the secondary literature often append the term “ancient” and there is little reason to doubt that the formulation predates written evidence. The King describes himself as ‘Patron, Protector and Supporter’ at the head of the Instrument of Foundation and this terminology is likely to have been adopted for the King’s toast at early Academy dinners. As for ‘Honor & Glory’, this may well pre-date the Academy itself. It is bi-partisan in tone, privileging neither the Academist party nor the Hogarthians and could, perhaps, date from the Society of Artists of Great Britain’s St. Luke’s Day dinners.

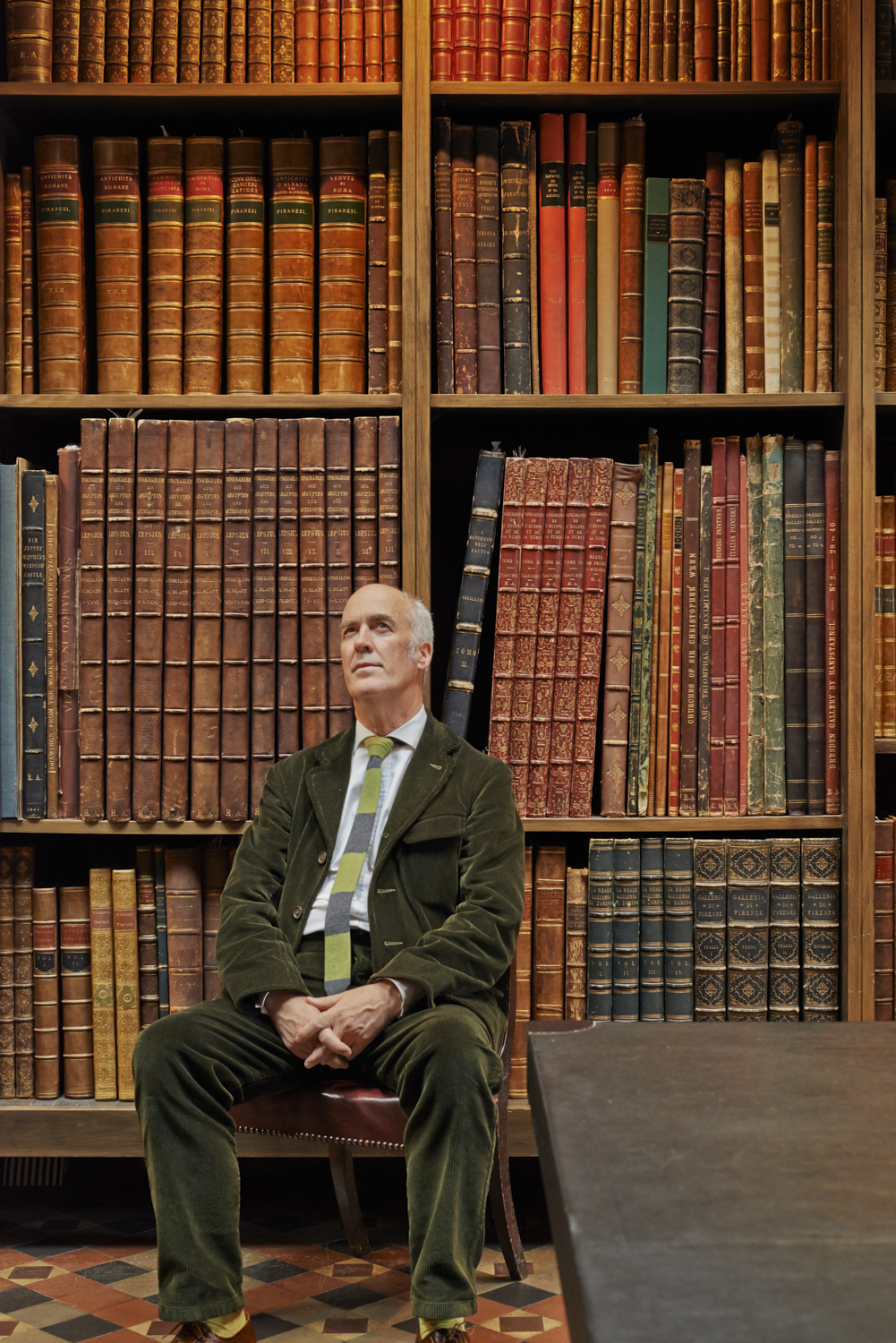

Gavin Stamp (3)

I only just made it to Gavin Stamp’s funeral, held – very appropriately – in St. Giles, Camberwell, George Gilbert Scott’s great masterpiece of the early 1840s, an appropriate place for the service as so much of Gavin’s life was tied up with the three generations of Scotts, including his book Temples of Power, published in 1979 with illustrations by Glynn Boyd Harte, which first bought the Bankside Power Station to public attention (and it was apparently Gavin who first suggested that it might be used as an art gallery). I luckily arrived in time to hear the eulogy which had been written by Jonathan Meades in language of magnificent convolution be delivered by Otto Saumarez Smith, adding an unexpectedly dramatic delivery to the oratory. I don’t think I have ever seen so many architectural historians all gathered in one place and had forgotten that Gavin was not only conservative in his architectural tastes, but co-wrote The Church in Crisis with Andrew Wilson and Charles Moore, so that we were able to enjoy the Lord’s Prayer (and the rest of the service) in the original language.

Charles I (2)

Ivan Gaskell in the Comments section of my blog asks the sensible and legitimate question as to whether or not it is right for art historians to focus on the range and quality of Charles I’s connoisseurship, his acquisition of the Gonzaga collection in 1629, and his use of Van Dyck to celebrate himself, his family and his particular style of kingship without obvious and explicit reference to the fact that his lavish personal expenditure, his suspension of parliament, his churchmanship, and his style of kingship contributed to civil war in the kingdom and the loss of his crown. Maybe it is a cavalier and not a puritan exhibition.

Charles I (1)

Although I have been watching our Charles I exhibition come together and gradually be installed, it was only last night that I was able to see it in its full glory.

First thoughts. I didn’t know the full scale of what has been lost. For example, a bust of Bernini based on the great Van Dyck triple portrait which was lost in the 1698 Whitehall fire. A Velázquez portrait which he commissioned when he visited Madrid in March 1623.

Second is the staggering quality and generosity of the loans from the Royal Collection. Of course, I know intellectually the quality of the Royal Collection from its published catalogues and exhibitions at the Queen’s Gallery, but even so, this did not prepare me for the number and range and scale of works lent, all of which were sold in 1649 and later recovered at the Restoration.

The third is the quality of the design, done immaculately by a French designer, Cécile Degos, using French paints.

New Cumnock Swimming Pool

We were taken to see the New Cumnock outdoor swimming pool, an initiative – only one amongst many – of the Dumfries House Trust which has brought new life to the local community by restoring not only the lido (1966), but the Town Hall as well:-

The Town Hall is Scots Renaissance 1888-9:-

Dumfries House (3)

Before I leave the subject of Dumfries House, I should say that I was very impressed by the amount of activity and new build on the estate. After long years when the estate was totally inaccessible, lived in by the Dowager Marchioness of Bute, it has now been opened up with a range of social enterprises in the surrounding park, including a cookery school and public restaurant, an outpost of the Royal Drawing School, a gymnasium and climbing wall, artists in residence, much of the activity contained in new, semi-industrial buildings.

This is the walled garden:-

And the roof of the the bunkhouse:-

Dumfries House (2)

Inside is a nearly perfectly preserved set of interiors of the late 1750s, complete with plasterwork ceilings, neoclassical chimneypieces and much Chippendale furniture, whose purchase is documented, including fine Chinoiserie girandoles flanking Lord Dumfries’s portrait in the dining room, a set of elbow chairs and pair of card tables in the Parlour, a desk in the room originally known as ‘My Lords Dressing room’, and, best of all, the padouk bookcase in the Drawing room. Chippendale had taken on a Scottish partner, James Rannie, in 1754, the year he published the Director. The furniture was dispatched by boat from London in late May 1759, and, on 29 May, Chippendale wrote a letter to say that ‘we ship’d your goods on board the Dilgence which saild on Sunday morning early… The contents of each case wt properdirections are given to ye Person who goes to put up the Furniture. We pay him a Guinea a Week’. It is an astonishing survival, narrowly saved from sale by Christie’s (the sale catalogues had been published), before the house and estate were bought lock, stock and bookcases by a consortium led by the Duke of Rothesay, following appeals by James Knox and Marcus Binney, in 2007.

Dumfries House (1)

I had been looking forward to visiting Dumfries House – a small-scale, mid-eighteenth-century, classical mansion, designed by John Adam, the oldest son and heir of William Adam, and his younger and more talented brother, Robert.

The house was built for William Dalrymple-Crichton, the fifth Earl of Dumfries, who was born in 1699, served in the army, and fought as aide-de-camp to his uncle at the Battle of Dettingen, having inherited the title from his mother the previous year. During the 1750s, following the death of his first wife, he devoted himself to the task of constructing a new house in consultation with friends and a neighbours, a model of the mid-eighteenth-century Scottish and Edinburgh élite (Boswell was brought up on the estate next door).

The first reference to his plan to build a new house appears in a letter the Earl’s lawyer wrote in 1749 to the effect that ‘Mr. Adam who I see now in town will with your Lop whenever you desire’. On 7 June 1750, he wrote, ‘I hope Mr Adam has given your Lordship full satisfaction. Is the house to go or not’. As the Earl’s lawyer, he was anxious about the likely cost: ‘I agree with your Lop that you need a new House, bit would not have your Lop go into an expense that would shorten your living comfortable’.

The process of design took some time and it was not until 19 March 1753 that Lord Dumfries was able to write to his friend, the Earl of Loudoun, that ‘Mr. Adam has at last finished the plans & estimates for the new house, but I have not yet seen them and of consequence have taken no resolution about them’. The drawings that accompanied the second estimate, dated March 1753, were drawn by Robert Adam, who was then acting as draughtsman for his older brother’s architectural practice, and he was co-signatory with his two brothers on the contract design dated 24 April 1754, before setting out on the Grand Tour. Lord Dumfries had already paid in advance for a copy of ‘The RUINS of the Emperor DIOCLESIAN’S Palace a SPALATRO in DALMATIA’.

Unfortunately, it was nearly dark by the time I got to see the south front of the house:-

You must be logged in to post a comment.