There is a relevance to what Eric Reynolds has done and achieved at Trinity Buoy Wharf over the last twenty years to the issues surrounding the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. What Reynolds recognised is that London cannot, and should not, rely solely on an economy of cappuccinos and international tourism: it should retain some element of the grit of the old riverside industries, of shipbuilding and of manufacturing and trade skills. He has achieved this by encouraging a culture of small-scale industrial entrepreneurialism. There is a lesson in this for us all, as Rupert Murray’s film showed.

Monthly Archives: February 2019

Trinity Buoy Wharf (1)

We went this evening to see a film about Trinity Buoy Wharf which I strongly recommend if and when it is shown more widely.

Shortly before the London Docklands Development Corporation was closed down in 1998, an area of derelict land on the north bank of the Thames beyond Greenwich was allocated to a trust on a 125-year lease and given to an enlightened property developer, Eric Reynolds of Urban Space Management, to administer. Unlike the big developers, he has retained all the existing buildings and encouraged creative people, including, in its early days, Thomas Heatherwick, to take leases. The result is to create an environment very different from most of London: full of artists, mechanics and inventors.

The film was funny and highly instructive as to how an urban environment can be developed in a creative way: there is the workshop which makes props for English National Opera, a branch of the Royal Drawing School, a school and lots of containers which are available at low cost to the people who enrich the life of the city. It’s a model of what is needed as artists are pushed further and further east.

Whitechapel Bell Foundry (2)

One of the benefits of the application to Tower Hamlets for a change-of-use of the Bell Foundry (as if it is not possible to maintain it as a bell foundry) is that the accompanying documentation contains a wealth of information, especially the Heritage Staement prepared by Alan Baxter, the conservation specialists.

The Whitechapel Bell Foundry is (or was) not any old foundry, but cast the Liberty Bell in 1752, the bells for Montreal Cathedral in 1843, Big Ben in 1858 (what could be more historically resonant than Big Ben?), and the Bell of Hope presented by the City of London to New York in memory of 9/11.

Historic England have given (paid) advice to the new owners on what they regard as a creative change-of-use from a working foundry into (another) ersatz wine bar. They think of the building solely in architectural terms, as a Grade 2 listed building, and claim that this is all they are allowed to do. But it is (or at least was until very recently) one of the most remarkable and well-preserved pieces of historical archaeology. Surely they, of all people, should be fighting to preserve it.

Tiger Rugs

I called in on the exhibition of Tiger Rugs at Sotheby’s. I hadn’t realised that it included examples of early rugs, like those which were shown at the Hayward Gallery in 1988:-

There are also modern versions, woven in India. One by Kiki Smith:-

By Francesco Clemente:-

And a particularly beautiful one by Anish Kapoor (all sold):-

Soho

I walked through Soho in the rain. I thought I knew it well, but keep discovering more side streets and back alleyways.

The doorcases in Dean Street (one is Black’s):-

In Meard Street:-

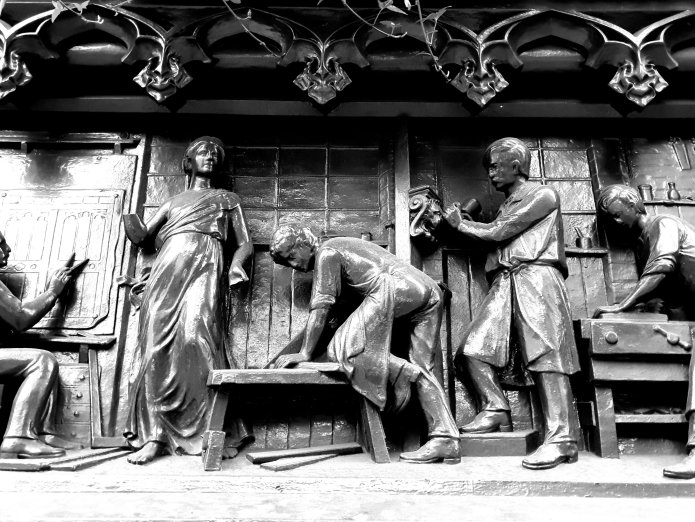

And the amazing Arts-and-crafts carving over the entrance to Liberty’s:-

Whitechapel Bell Foundry (1)

The new owners of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, Raycliff Capital, an investment firm based in New York and owned by Bippy Siegal, a venture capitalist, have now put in for planning permission to change its use from being the last working, fully functioning bell foundry in London, with its origins in the sixteenth century, to a themed café/bar alongside a new, multi-story boutique hotel.

The issue which will face the planners is: is this change of use legitimate and justified ? The previous owners have argued, and will, no doubt, continue to argue that there is now little demand for church bells and that it had become impossible for them to maintain the production of bells so close to the centre of London, so that a change-of-use is justified.

However, the United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust has put together an entirely credible alternative scheme for reinstating a foundry in the original – and architecturally wonderful – ground floor space, employing some of the workmen who worked there before. Instead of being turned into a café/bar/leisure centre, it would return to being a fully functioning foundry, making work for artists.

So, the question is: which will Tower Hamlets prefer ? What, in planning terms, is the ‘optimum viable use ‘ ? It’s a test.

Éric Hazan

A long day travelling to the Verbier Art Summit – made longer by the fact that my flight from City Airport was cancelled – enabled me to read quite a lot of Éric Hazan’s The Invention of Paris, an admirable and highly detailed exploration of the quartiers of Paris through the eyes, mostly, of nineteenth-century writers, including Baudelaire and Balzac. For much of his career, Hazan was a cardiovascular surgeon and his approach to the study of the city is surgical, approaching its streets with a literary stethoscope, listening to its heartbeat. He has done a more recent book, A Walk through Paris, which is full of reminiscence, but the Invention of Paris is a deeper historical analysis, which enabled me to escape Heathrow into the seventeenth-century Marais, the nineteenth-century arcades, and the destruction of Les Halles by Pompidou.

Watercolour World (2)

Having attended not one, but three launches of Watercolour World yesterday, I learned a great deal more about how widespread its use was as a medium of documentary record.

The first was the extent to which its use was pioneered by the army in the 1740s, following Thomas Sandby’s appointment as private secretary and draughtsman to the Duke of Cumberland, who took him with him to record the Battle of Dettingen and made records of the enemy encampments at the Battle of Culloden. In the late eighteenth century, it was regarded as a useful skill in the arsenal of an army officer, making it possible to document and survey military fortifications.

The next key development was the establishment of the Whatman paper milk in Maidstone in 1740 which led to the production of good quality wove paper in 1756.

The third key development was the invention of the paint cake in 1781 by William and Thomas Reeves, which made it possible for amateurs and professionals to go out into the world with a box of watercolours in their pocket to record the appearance of volcanoes and balloons and all other forms of natural phenomena.

You must be logged in to post a comment.