The developers of the new plans for Liverpool Street Station, Sellar, are, once again, holding a public consultation which this time is relatively easy to find if you know where to look – it’s in a booth under the escalators opposite Boots on the way out to Broadgate.

There is an illuminating model and some of the most amazingly sophisticated computer graphics that I have ever seen, showing exactly how the 1980s additions will be swept away in order to create a double deck passenger concourse and a gleaming new twenty-first century entrance from the south.

Having now looked at the scheme, I can see some benefits:-

1. The current station is very overcrowded.

2. Disabled access is pretty appalling.

3 The run of shops which were put in during the 1980s block the wonderful views of the original nineteenth-century railway sheds.

4. Opening up public access to the ballroom of the Great Eastern Hotel is a public benefit.

It is, I think, incontestable that the station would benefit from a bit of rethinking and a lot of investment.

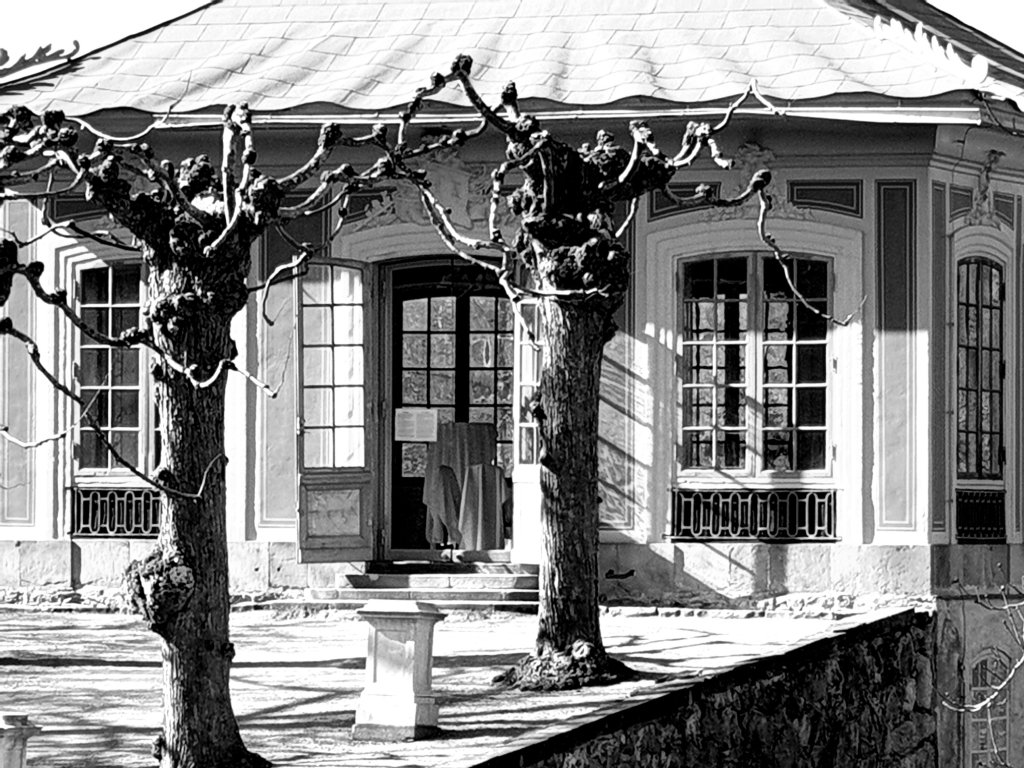

But there is one simply gigantic problem with the scheme as currently proposed which the consultation does not, for obvious reasons, make clear. The way of paying for it is by building gigantic tower blocks directly on top of the station and the Great Eastern Hotel.

The precedent used to justify this is the work the same developers, Sellar, have done at London Bridge Station and are now doing at Paddington. But there is a big difference. At London Bridge, the Shard has been built alongside but independent of the station. At Paddington, the new building, The Cube, is separate from the station. The idea of just building tower blocks on top of a Victorian building is frankly repulsive and perhaps not surprisingly is not shown anywhere in the glamorous promotional video.

I feel John O’Mara of Herzog de Meuron should go back to the drawing board and come up with a plan which is elegant, as is the Shard, and not lumpen – monster slabs dropped on top of two historic buildings:-

You must be logged in to post a comment.