I stopped on Clee Hill to look southwards towards the Malvern Hills because of the light on the distant fields:-

I stopped on Clee Hill to look southwards towards the Malvern Hills because of the light on the distant fields:-

I wanted to see the Temple of British Worthies close up: such a strange and unexpected grouping. Some one would expect: William III, not Queen Anne, as the saviour of democracy ‘preserved the Liberty and Religion of Great-Britain‘

Thomas Gresham I did not expect, a representative of commerce – ‘the commerce of the World’:-

And John Locke,’best of all philiosophers, understood the powers of the human mind’:-

The Palladian Bridge:-

And the Gothic Temple:-

I spotted a sign en route to mid-Wales for Victoria Plums – I think it was just short of Cleobury Mortimer – and drove down a track through an orchard to where one could buy plums by sounding one’s horn:-

As a result of appearing on Newsnight to discuss some if the issues surrounding the thefts at the British Museum, I have, perhaps not surprisingly, got interested in what, and how, things went wrong.

One issue which has not so far been mentioned, partly because the news coverage is not very analytical, is what went wrong with the procedures of audit. The British Museum is not a private institution, but is still, to a significant extent, state funded. As a result, it will have been subject to very regular processes of internal and external audit which will inevitably have covered issues of security and collection care on a routine basis. So, who, one wonders, has been undertaking their audit over the last fifteen years and what were their recommendations ? It used to be that the National Audit Office undertook regular reports, as they did in 1988 when they were highly critical of the V&A, which led to the establishment of computerised documentation of the collection, but much less critical of the British Museum which survived scrutiny. This was over thirty years ago in the early days of computerised collections management. It would be interesting to know what the recommendations of audit have been and whether they have been followed, because it seems a touch implausible, as has been implied in the press, that there are roughly 6 million objects still lying about in the stores which have not been properly documented in an internal inventory, not least because the online catalogue of the Department of Prints and Drawings, which I use routinely, is exemplary.

I was asked to comment on Newsnight about the thefts at the British Museum.

There are some odd aspects to this story, if one is to believe the information about it which is available online (for understandable reasons, not much is).

The first and most obvious is that the thefts were first reported to the museum by Dr. Ittai Gradel, a Danish scholar of antiquities, in February 2021 who was able to identify (from the museum’s own online catalogue) antiquities – apparently classical gems with a known provenance, including from the Townley Collection (some were listed in the museum’s published catalogue) – which were available for sale on ebay and was even easily able to identify who was offering them for sale because the person used their twitter handle ‘Sultan 1966’. At this stage, all the museum’s alarm bells should have sounded. Theft is the worst thing that can happen in a museum and there must have been well-established procedures for investigating and dealing with theft. Someone apparently conducted an enquiry into the reported thefts and discovered that the three objects which had been reported missing were not missing after all. So how could this have happened, if, as now appears, the objects had already been sold ? The most likely explanation must be that the investigation was conducted by the museum’s curator of Greek and Roman antiquities, who was the person most qualified to know. The museum decided that nothing wrong had happened, reassured Dr. Gradel, and no further investigation was undertaken until it was discovered more recently that up to 2000 objects had been stolen and offered for sale, a catastrophe for the museum in every way.

The second thing which is odd is that the thefts were apparently also reported by one of the trustees, Sir Paul Ruddock, to the museum’s chairman in October 2022, nearly a year ago, presumably because it was by then well known to large numbers of people within the museum and its wider scholarly community that the thefts had taken place and possibly still were. At this point, one might think that it could have been sensible to involve the police, both in order to prevent further thefts and, also, if possible, to facilitate the task of recovery, which will be difficult, but presumably not impossible since the purchasers of the objects will have been recorded by ebay. Did this happen ?

A committee of enquiry is being conducted by Sir Nigel Boardman, a recently retired trustee. He needs to look carefully and openly about what went wrong, which will require some forensic investigation and a lot of soul searching.

I am posting a link to an event which is being held in Hackney on Thursday 7th. September to celebrate the publication of a volume of essays about the life and work of the late David Lowenthal, which includes a short afterword I wrote about the influence of The Past is a Foreign Country on the V&A/RCA MA Course in the History of Design and in the heritage sector more widely in the 1980s, particularly through a seminar which David and Peter Burke ran at the Warburg Institute (Join us for the launch of David Lowenthal’s Archipelagic and Transatlantic Tickets, Thu 7 Sep 2023 at 19:00 | Eventbrite).

I hope that the event will be an opportunity to celebrate David’s life and work, as well as his academic writings, and that as many of you as possible will be able to come.

I have been preoccupied by the discovery that macaroons were first invented in the eighth century:

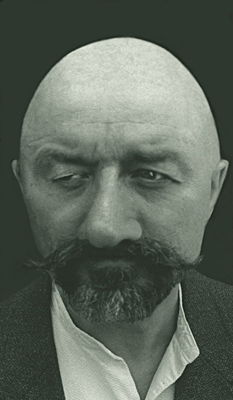

I am very sorry to hear of the death of John Goto, a remarkable photographer:

I first came across his photographs of Prague – I think at the ICA – and commissioned him to document the changes at the National Portrait Gallery in the 1990s. He did this with a Russian panoramic camera which introduced a great deal of distortion, but they were, as I had hoped, much more atmospheric than most documentary photographs. Then, in 2002, we walked in to Tate Britain and found a room full of his works from his series ‘Loss of Face’ which were devoted to digital images from rood screens damaged on the orders of the Cromwellian iconoclast, William Dowsing. We bought four of them and have lived with them ever since:-

You must be logged in to post a comment.