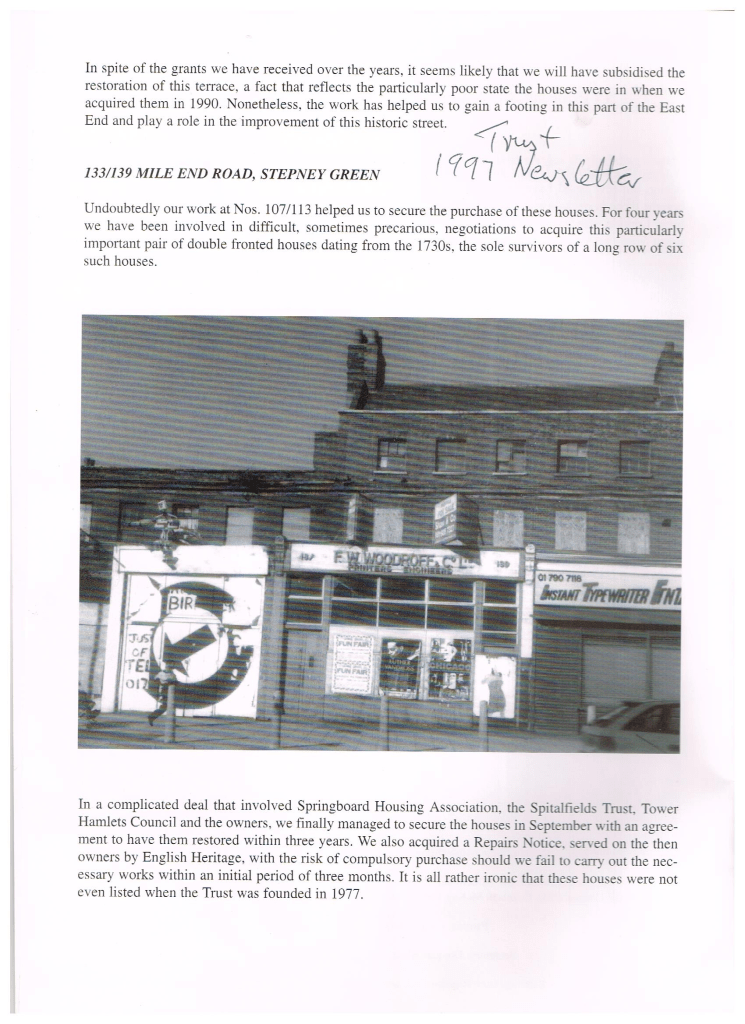

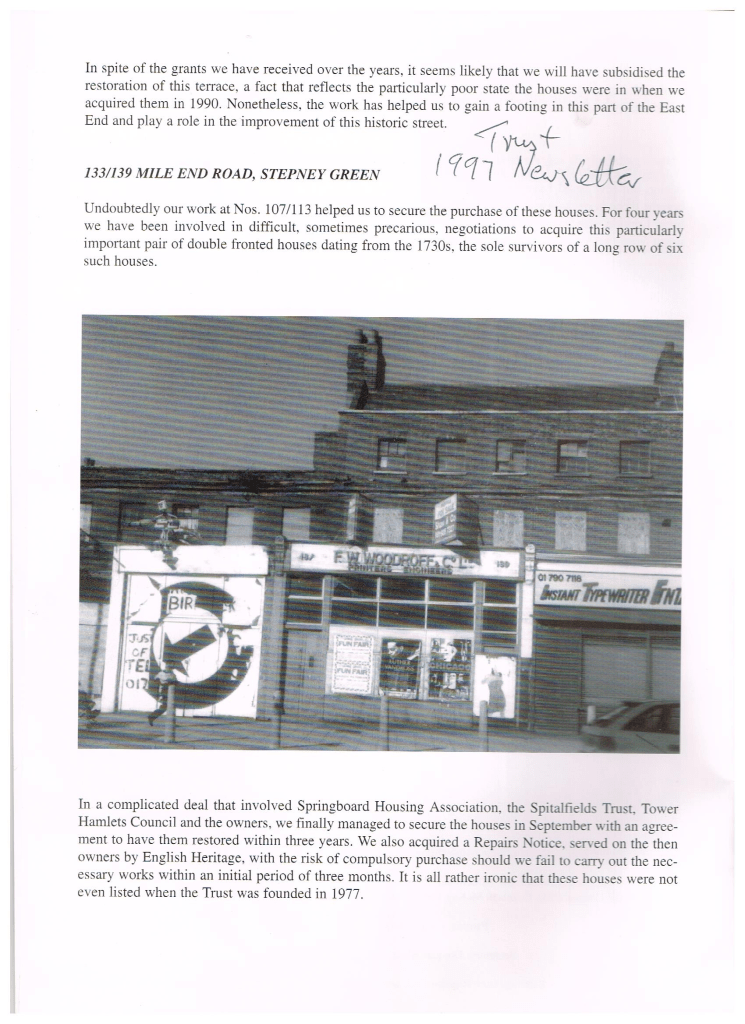

I have been sent a picture of our house as it was in 1997 when it was acquired by the Spitalfields Trust. It describes how the houses were acquired and the photograph shows the state they were in at the time, as well as the row of shops in front:-.

I have been sent a picture of our house as it was in 1997 when it was acquired by the Spitalfields Trust. It describes how the houses were acquired and the photograph shows the state they were in at the time, as well as the row of shops in front:-.

We walked through the rest of St. John’s, backwards, starting with New Court by Thomas Rickman:-

Good Gothic detailing, as one would expect from the scholarly Rickman:-

Across the Bridge of Sighs:-

Coffee in second court:-

Then out onto the backs:-

We were given a comprehensive and fascinating tour of the Cripps Building, which I realised was only completed in 1967, five years before I matriculated. I don’t remember being very aware of it. It anyway fits pretty discretely into its site in between Thomas Rickman’s New Court and Edwin Lutyens’s building for Magdalene College next door.

We arrived from the east, from the car park, not the sequence of medieval courts. It has an attractive austerity, the staircases treated in a sculptural way:-

It is all very reticent and carefully considered:-

The college is in the process of relandscaping it, so it is not so easy to get a sense of its larger dimensions:-

Its architect, Philip Powell, was the nicest, most charming and modest of men and the architecture is viewed, rightly, as thoughtful, contextual. It deserves a close look.

It’s Roy Strong’s 90th. birthday today. The Critic have kindly posted the article I have written for its August/September issue in his honour and to remind people of what we owe him.

Happy Birthday, Sir Roy !

I have just received an advance copy of David Cannadine’s festschrift – Institutions, Individuals and Modern British History, edited by Jonathan Parry and published by The Boydell Press.

https://share.google/ljAFCPMTAclRMiC7n

I have only had time so far to read Parry’s introductory account of Cannadine’s remarkable career. Parry implies that Cannadine modelled himself on the career of Jack Plumb, the worldly Master of Christ’s who must have helped to get him elected to a fellowship at Christ’s when he was appointed in 1977 to an Assistant Lectureship in British eighteenth-century history, an interesting appointment for someone whose PhD was on late nineteenth-century landownership. Possibly. But at that stage of Cannadine’s career, he seemed more influenced, as Parry also makes clear, by the work of Lawrence Stone at Princeton and H.J. Dyos at Leicester; and, as it happens, I think of Linda Colley, Cannadine’s wife, as more obviously a product of the Plumb school having done her PhD under him on the early eighteenth-century Tory party.

Anyway, the book is a rich feast for anyone who is interested, as I am, in the relationship between individuals and institutions and it includes essays on two other Cambridge historians – Noel Annan, author of a study of the intellectual aristocracy, and Owen Chadwick, who is always said to have turned down every bishopric offered him.

But, it’s not cheap.

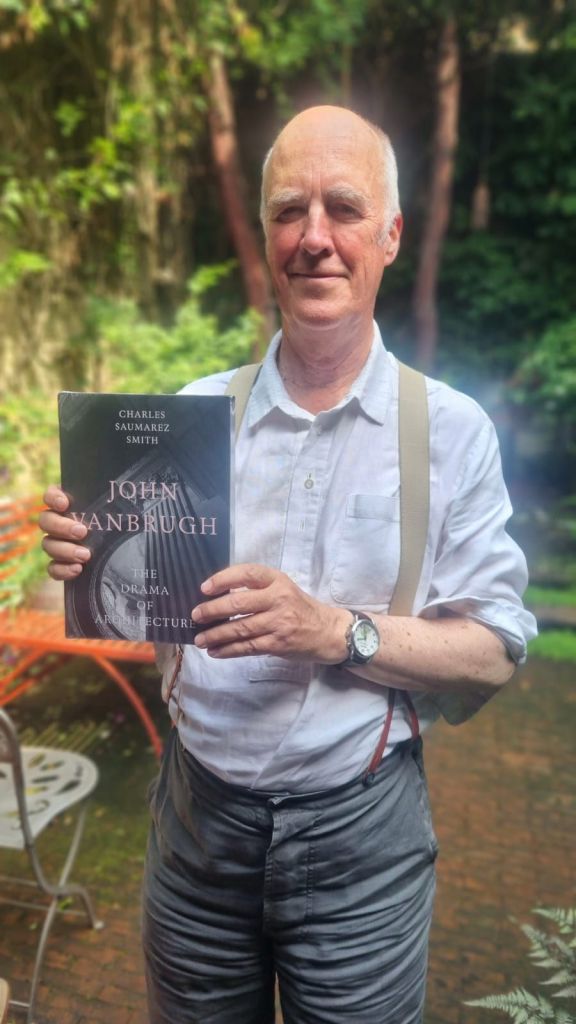

I have just been on my bicycle to the offices of Lund Humphries to pick up one of the first copies of my book, John Vanbrugh: The Drama of Architecture, just arrived from the printers in Bosnia.

This is, as every author knows, an exciting moment. Instead of staring at it on screen for the last four years, it is a reality. And Lund Humphries have done a really wonderful job in terms of its production. White paper. Matt photographs. I already knew that the designer, Mark Thomson, had done a brilliant job in terms of its layout, mixing colour and black-and white, double-page spreads, drawings and contemporary portraits, giving the reader a proper sense, I hope, of the gestation of the work and of Vanbrugh’s friends, allies and clients. David Valinsky has taken excellent photographs of the three greatest surviving houses – Castle Howard, Blenheim and Grimsthorpe.

You are all invited to the launch at the Wigmore Hall on November 20th:-

https://www.wigmore-hall.org.uk/whats-on/202511201200

Please come.

Meanwhile, copies can be pre-ordered from Lund Humphries.

Or Amazon.

We walked out to the mausoleum.

Along the terrace:-

To the Temple of the Four Winds:-

Across the fields:-

Up the steps:-

Into the chapel:-

There is no grander or more architecturally powerful space in England:

It was a wonderful experience to go to Castle Howard after a day of talking about Vanbrugh’s role in its design. I find it easy to believe that Vanbrugh was responsible for its conception and initial design, without necessarily needing Hawksmoor’s help; but then the Great Hall is so spatially complex. So where did the ideas for it come from ? It doesn’t feel like Wren. Paris ? From prints ? Or Vanbrugh’s recollection of buildings he had visited before returning to London in 1693:-

Tim Abrahams of Machine Books is doing a great job in publicising my forthcoming biography of Vanbrugh:-

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” In an era, when we have lost our understanding of the past’s remove, when events back then, must be judged by the values of right now, we struggle to find the importance of art and architecture which do not accord with our present preoccupations.

Swimming against this tide is Charles Saumarez Smith’s wonderful book about the great British architect John Vanbrugh – and he was great, Wren and Hawksmoor fans – which neither judges him by the moral standards of our age nor asserts an appreciation of him as somehow essential to preserving our national selfhood.

He is though, in Charles’s description, a mercurial figure who helps form Britain’s understanding of architecture’s potential; what it can do in symbolic terms for different political entities including the state.

You must be logged in to post a comment.