I have been sent a PDF of the diary of Perry Rathbone, Director of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in the 1960s, which has been published by his daughter, Belinda. It gives a good sense of the life of a museum director – hectic, torn between travel, seeking acquisitions, visiting exhibitions and cultivating donors, without much time for self-reflection, or even writing a diary, except for the occasional set pieces as when Kennedy is shot.

It is picture of upper crust Boston as it used to be – a lot of time entertaining, dressing for dinner, going to clubs. Much of it is routine sociability about people now forgotten, but there are occasional moments which make one sit up. I had not realised that Josep Lluís Sert, the Catalan architect, was Dean of Architecture at Harvard and responsible for some of the big buildings in Harvard Yard as well as the Fondation Maeght. There is quite a bit about historic preservation, and while Rathbone is interested and knowledgeable about contemporary art, he hates Corbusier’s Carpenter Center next door to the Fogg. He is contemptuous of poor old W.G. Constable, the first Director of the Courtauld Institute who went to be Keeper of the Paintings Department in Boston and who he keeps meeting at parties. He was also uncomplimentary about Bernard Berenson, quoting Meyer Schapiro who wrote that ‘Business was the concealed plumbing in Berenson’s house of life’. There is an interesting comment as he packs up their holiday cottage on Cape Cod that ‘The Cape changes – how swiftly ! I see a complete surrender of the holdings of the old Yankee higher order and a ruination of the ‘Old Cape’ we have loved’.

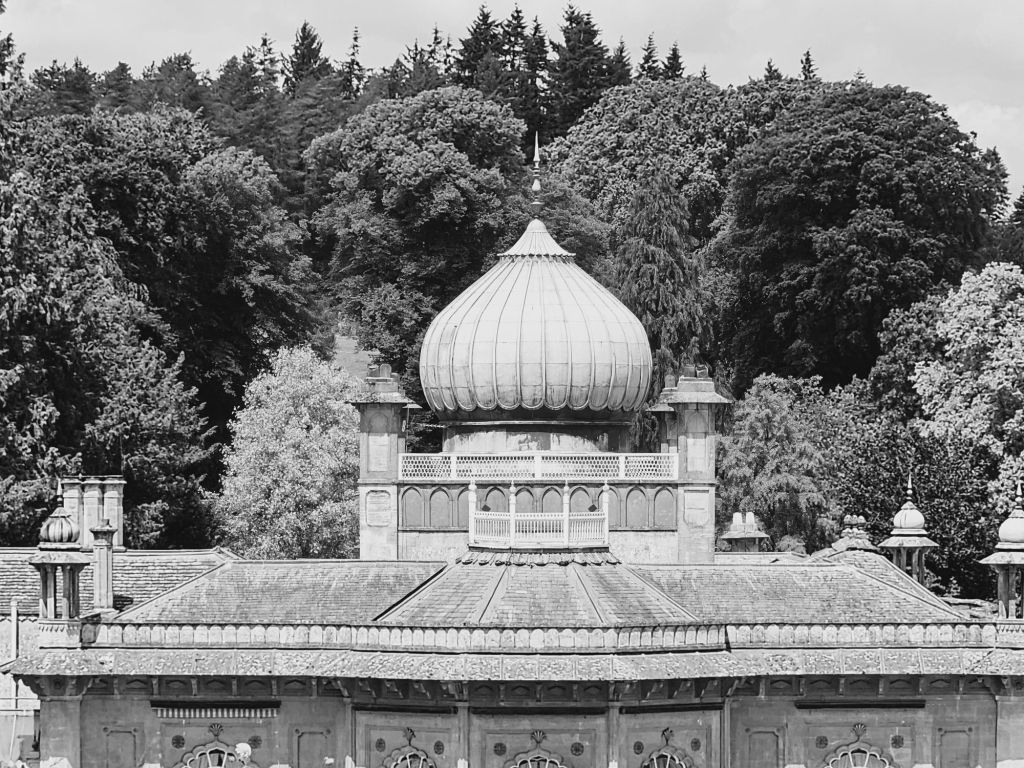

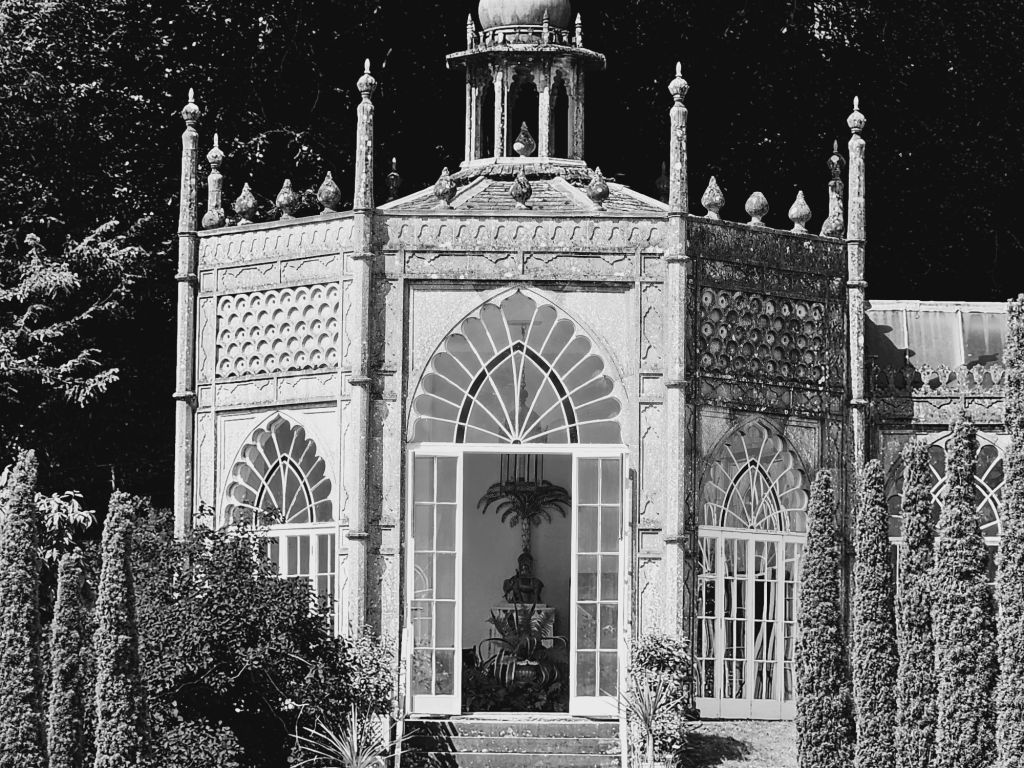

Rathbone was a product of Paul Sachs’s course at Harvard on ‘Museum Work and Museum Problems’. What comes across is that the requirements are not so much connoisseurship as stamina in maintaining a hyper-active social life, staying each summer with Peggy Guggenheim in Venice and Henry P. McIlhenny in his castle in Ireland, waiting for rich people to die in the hope that they might bequeath their collection to the MFA.

You must be logged in to post a comment.