Limehouse Basin is much shrunk from what it once was. It was originally constructed as the Regent’s Canal dock in 1812, but the Regent’s Canal itself was not completed for another eight years, by which time the dock had been enlarged to accommodate the coasters which brought food and coal from East Anglia and the north of England to feed and heat the greedy capital. By the mid-nineteenth century, it was already too small for the new steamships and so was used instead for the construction of lifeboats. When we moved to Limehouse in the early 1980s, it was much larger than it is now, a disused expanse of vacant water, subsequently filled in and converted into a marina:-

Monthly Archives: January 2015

Isle of Dogs

I took myself on a giro round the Isle of Dogs this morning. Partly because it’s a while since I’ve travelled on the squeaky Docklands Light Railway as it winds its way through the tower blocks. Partly because I wanted to remind myself of the false rusticity of the Mudchute (actually, at least in its allotments, a remarkably effective illusion of rusticity):-

Spiegelhalter’s

I have been alerted to anxieties round the fate of Spiegelhalter’s, the small jewellery store, which resisted the blandishments of Wickham’s, the neighbouring department store, to sell up and so Wickham’s simply constructed its grand 1927 neoclassical façade round it. In the 1960s, this was celebrated by Ian Nairn as a ‘triumph for the little man, the blokes who won’t conform. May he stay there till the bomb falls’. Now, the bomb may be about to fall and what little survives of Spiegelhalter’s replaced by a glass atrium. It can’t be listed because it’s of no obvious architectural importance (and Wickham’s itself hasn’t been listed despite its significance as a building type), so there is pressure instead to persuade Tower Hamlets to resist any such plans. There is a form to sign online.

Thomas Okey

One of the people I wasn’t familiar with in the William Morris exhibition was Thomas Okey, whose portrait is shown when he was Master of the Art Worker’s Guild and who remembered Morris lecturing at Toynbee Hall. What I hadn’t realised in seeing the portrait is that Okey was an early product of an east end education: the son of a basketmaker in Spitalfields, he was educated at St. James the Less National School in Sewardstone Road. Whilst working as a basket maker, he taught himself French, German and Italian, attended evening classes at Toynbee Hall, and began to write books about Italian architecture, as well as An Introduction to the Art of Basket-Making, published in 1911. In 1919, he was appointed as the first Serena Professor of Italian at Cambridge. Quite a career.

Boundary Estate

The Boundary Street Estate was built in the 1890s by the London County Council as a way of clearing out The Nichol, a largely criminal district which was the subject of Arthur Morrison’s A Child of the Jago, published in 1896, and Raphael Samuel’s classic East End Underworld. It was the first big estate designed by the Working Classes Branch of the Architect’s Department at the LCC and has blocks designed by different architects, all of which are centred on Arnold Circus and its bandstand. I hadn’t previously noticed the quality of some of its Arts-and-Crafts detailing, including the lettering:-

Moths

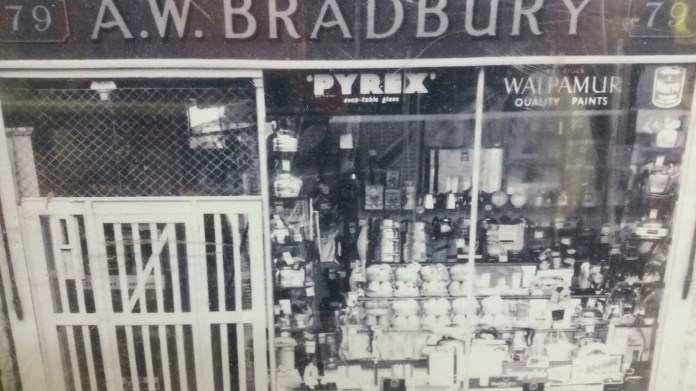

As the season of moths approaches, I was tipped off that the best place to buy all sorts of moth repellent, including moth balls, is an old fashioned hardware shop called A.W. Bradbury at the top end of Broadway market. There, indeed, just inside the door on the left, is a whole section devoted to the destruction of moths – balls, spray and traps. I plan to use them all.

Lakeview Estate

I was reminded by Otto (or maybe it was castigated for my ignorance) that there is another estate by Lubetkin just south of Victoria Park. Indeed, there is, with some of the same hallmarks as the nearby Cranbrook Estate, which is visible along the Hertford Union canal, but Lakeview has distinctive side pavilions which look as if they derive from rural Slovakia:-

William Morris (2)

I realised last night that I was in danger of missing Fiona MacCarthy’s admirable exhibition Anarchy and Beauty: William Morris and His Legacy 1860-1960, which closes this weekend. So, I made my way back to the NPG amidst the Friday evening crowds (there’s a lot of reading as well as looking to be done). What comes across very forcefully is the amazing range of his activities: writer (now neglected); weaver; printer; manufacturer; political agitator; designer. Of course, he was helped by having a private income, but it’s still an amazing record. Not least, I hadn’t realised the extent of his influence on the Garden City movement, Ebenezer Howard, Henrietta Barnett, George Lansbury et. al.

William Morris (1)

We went to a brilliant lecture by Edmund de Waal on the influence of William Morris on himself and others. He traced the influence of Morris’s writings and teachings on generations of craft practice, based on the example of a rock solid medievalising table which Morris constructed for himself when he was living in one room in Red Lion Square (hand built and communal). De Waal went on to describe the ways in which the writings of Morris were absorbed by Bernard Leach and other members of the Japanese craft tradition in Kyoto, including Shoji Hamada; Continue reading

Frederick Wiseman

I have spent the last couple of days immersed in watching, and thinking about, Frederick Wiseman’s long film about the National Gallery for a brief (very brief) appearance on the Today programme. His technique is rigorously anthropological : he immerses himself in the life of an institution for three or four months, films everything as scrupulously as possible, and then sees what emerges through a long editorial process. The result is an extraordinarily detailed set of observations as to how the National Gallery and its staff at all levels, and particularly its education department, explains and interprets the paintings in the collection to different audiences, from the blind to a single individual donor. I think the lesson of the film, if there is a lesson, is that the nature of individual experience of paintings is ultimately unknowable. The film opens with a long slow sequence of paintings viewed silently without interpretation; and it ends with another long slow sequence set to ballet. These silent sequences come across as a more profound experience than any amount of historical, cultural or contextual explanation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.