I walked back through the cemetery and took what I thought were beautiful photographs of it in autumn light. But they didn’t really come out, so I have doctored them, which I don’t really approve of:-

Monthly Archives: November 2017

The Limehouse Cut

We walked up the Limehouse Cut today to its junction with the River Lea where there is an area of still industrial wasteland, looking across to the gasholders and north under the railway viaduct to Three Mills:-

East London (2)

I have now finished reading Maryam Eisler’s study of the East London creative community in her book Voices (actually, it could be called Vices) which studies the range of different creative types who have inhabited East London over the last three decades. What I realised and is obvious is the extent of inward settlement and migration, all of which has given vitality to the area. But what I also began to notice is how little the existing community is referred to. Doreen Golding, a Pearly Queen, describes how ‘Most of the old white English, the Pearlies, moved out to Essex, Basildon and Southend’. Colin Rothbatt describes how one of his neighbours threw a brick over the wall during one of his all night parties. And Jack Leigh, a retired gangster, describes how ‘The ’60s and ’70s were wonderful. The Krays were in Bethnal Green and we were in Roman Road…There was a sense of belonging because we loved one another and relied on each other’. It would be interesting to know a bit more of the views of those who have been displaced.

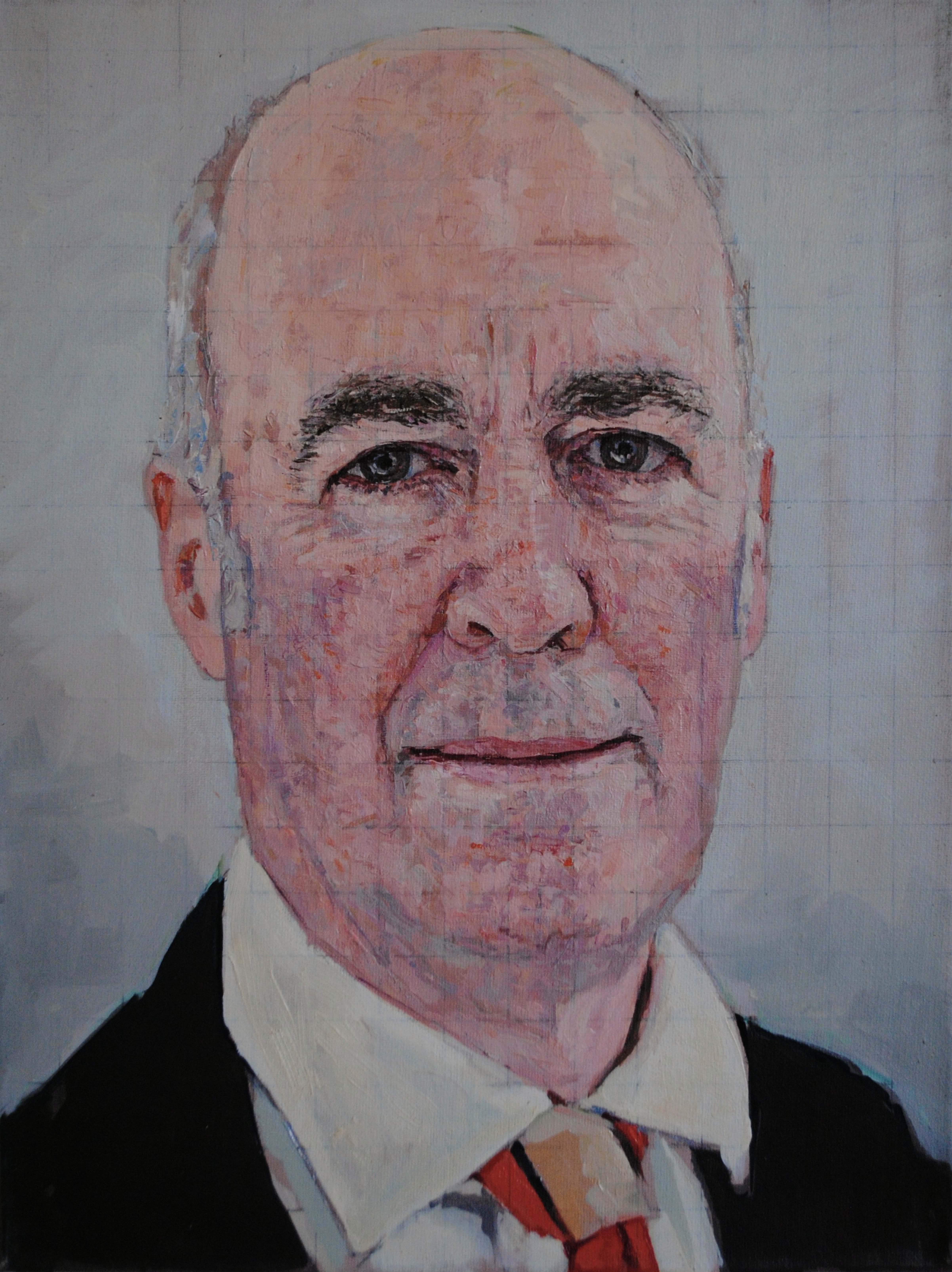

John Russell

I have been reading John Russell’s book about Shakespeare’s Country, which I had not known existed: his first book, published in Spring 1942, when he was only 23, having recently graduated from Oxford and was working as an unpaid assistant for the Tate, which had been evacuated to Eastington Hall in Worcestershire. It belongs to an odd genre of countryside writing much promoted by Batsford – not a guidebook, because, as I learn from the Preface, publishing a guidebook during wartime was illegal; nor was Russell a very obvious person to have written the book, as he had been brought up not in Worcestershire or Warwickshire, but in Strawberry Hill in London. In fact, the text is as much literary as architectural. The first chapter is devoted to a life of Shakespeare (one of the illustrations is of the original Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, a magnificent castellated structure, looking as if it belonged in south Germany). In later chapters, he is most enthusiastic about places with literary associations, like Hagley, admired by William Shenstone, and Sion Hill, the birthplace of the typographer, John Baskerville. I like the description of Cheltenham: ‘to coast through is crescents, promenade, and acacia-shaded avenues is to hear an old, thin, bony music, as if someone in an empty house were to play upon a wooden-framed piano, a sonata of Weber’. The qualities of Russell’s writing were much admired by John Piper, who became a lifelong friend, and Logan Pearsall Smith, who encouraged him to be a full-time writer.

The London Library

I’ve just got my copy of the winter edition of The London Library Magazine, which includes an article I wrote about the discovery of what I thought was a first edition of Hobbes’s Leviathan on the open shelves and the fact that, in the early 1980s, it was possible to borrow it. The article only half conveys my gratitude to the library during that period of my life, when I was a solitary Ph.D. student, trying to teach myself about late seventeenth-century intellectual thought in order to understand the cultural milieu of Castle Howard. It was in what is now regarded as the bad old days when Ph.D. students were given almost complete freedom to read round their subject with no pressure whatsoever to complete the research, let alone to publish it (actually, I only remember the opposite). The London Library was like a constantly open dish of pleasure.

Hyde Park

Lizzie Treip

I had not expected to be so affected by the memorial event in the local Ecology Pavilion for a local friend and neighbour, Lizzie Treip, who died of MS, aged 58. It was not as if I knew her so well. I used to meet her on Saturday mornings at the local farmer’s market and sometimes at social events, which she or we had arranged. It was partly the unspeakable cruelty of the disease, both spoken and unspoken, which influenced her life profoundly, but not her love of music and literature and friends; the fragility of her life before the disease struck and her resilience mostly in confronting it; and partly the memory of her life beforehand, its ordinariness, the pictures of her on holiday, when she was small and her children were small.

Herbert Cook

I have just refreshed my memory about Sir Herbert Cook who owned Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi unawares for most of the twentieth century. It was his grandfather Francis, a wealthy textile merchant, who must have bought it in 1900 from the connoisseur John Charles Robinson and then bequeathed it to his son Frederick who in turn left it to his son Herbert on his death in 1920. Herbert had helped establish the Burlington Magazine and was one of the founders of the Natiinal Art-Collections Fund, so his collection would have been well known to art connoisseurs of the time. But although he was a Trustee of the National Gallery during the 1920s, his collection, left to his two sons, was dispersed after his death.

Salvator Mundi

I have just been asked my opinion (on Sky News) on the sale of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi for $450 million (including commission). It is indeed a staggering price, particularly given that it was sold in 1958 from the Cook Collection in Richmond for £45. It was then heavily overpainted and regarded by experts as a copy after Boltraffio. It surfaced in the United States in 2005 and was apparently sold for $10,000. It was only once it had been cleaned and restored by a consortium of dealers that it was accepted by scholars as authentic and shown as such in the National Gallery’s Leonardo exhibition in 2012. The estimate this time round was $100 million, which itself was more than any other Old Master painting has previously sold at auction.

Degas (3)

Marina Vaizey has rightly reminded me that, at the same sale that Charles Holmes failed to acquire Degas’s Combing the Hair, but did acquire three works by Ingres, including Monsieur de Norvins, and fragments of Manet’s Execution of Maximilian, so Maynard Keynes who had negotiated the special grant of £20,000 from the Treasury was also, and more officially, a member of the International Financial Mission led by Austen Chamberlain, also attended the sale, and himself acquired a study by Ingres, two paintings by Delacroix and a Cézanne Still life with apples (now owned by King’s College, Cambridge and on loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum) which he had wanted Holmes to acquire for the National Gallery. Both Keynes and Vanessa Bell were scornful of Holmes’s aesthetic myopia (the description used by Quentin Bell), but I have always been rather admiring of the fact that Holmes managed to acquire some great pictures while Big Bertha was booming in the distance. The story of Keynes’s trip and of him leaving the Cézanne in a hedge at the bottom of the Charleston drive was told by Quentin Bell in A Cézanne in the Hedge and other memories of Bloomsbury and Charleston.

You must be logged in to post a comment.