In the interests of the historical record, I am posting a piece I wrote for the RA’s in-house magazine about the experience of watching visitors enjoy the new building in the first few days:-

I’ve been asked to record my reactions to the new building. It happens that the request has arrived just as I have sat down to a cappucino in the Casson Room (buns are either off the menu or have all been eaten) after walking round to get a feel for our visitors’ response.

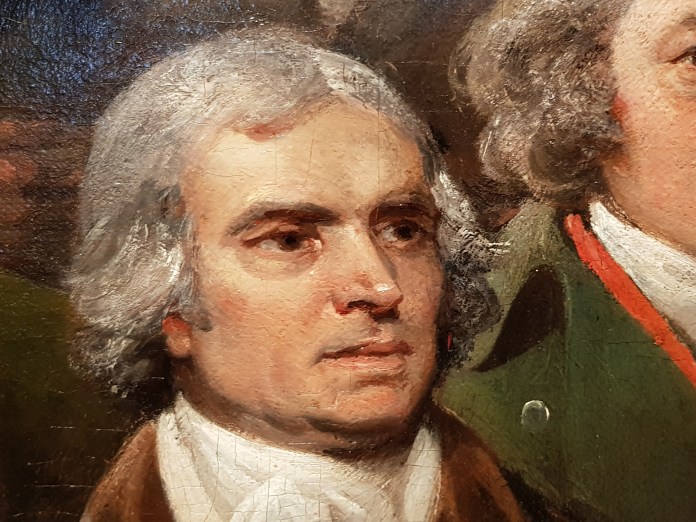

I enjoyed going round, not least because appearing on ‘The Private Life of the Royal Academy’ means that many more Friends recognise me and come up and chat, including Sandy Wilson’s first wife. I see them doing a double take and then ask a question to check that I’m real.

I was particularly pleased to see that the Dorfman Senate Room was packed in the middle of the afternoon even though you can only get beer, not tea. The space is humanised, literally as well as metaphorically, by being used.

I’m delighted by the trio of commercial spaces on the ground floor, which strike just the right balance between being clearly commercial, but also appropriate to the atmosphere of the building – the Poster Bar which has been designed to be like the bar of an Eastern European railway station, the Personal Shopping space with its plan chest, and the Newsstand with the latest art magazines (and, by the way, buy a card, write it, and have it posted for you – a lovely idea):-

One of the things that many people have remarked on is the centrality of the Schools and the way that this changes people’s attitude to the Academy. Of course, as the President says, this was the whole point of the scheme. But the theory can be different to the practice. I had not anticipated how key it is to the experience, mixing new art with old, the anarchic with the respectable, giving a frisson as one travels through the vaults into the Weston studio. It puts practice at the heart of the Academy in a wonderful way.

Another thing that has given me incredible pleasure is seeing staff sitting out in the sun eating sandwiches under the pleached trees of the Lovelace Courtyard.

After many years of staring at ground plans and CGIs, the experience is suddenly real, like a cartoon which has sprung into life.

But the real test will be 10 o’clock on Saturday when the first visitors walk in.

You must be logged in to post a comment.