We had a send-off for Gillian Ayres, no church service, just a semi-institutionalised wake. It was quite clear that we should have served gin and tonic, not elderflower cordial, because nearly every speaker referred to that as her favourite drink, along with the sixty cigarettes a day. The President spoke, her son Sam, Shirley Conran, her accountant, a lawyer who collected her paintings: all made clear what a wonderful, anarchic, anti-establishment, warm-hearted rebel she was, as a person as well as in paint.

Monthly Archives: October 2018

Argyll House

I didn’t include Argyll House in my description of Westcliff-on-Sea because I couldn’t find out anything about it: that’s because I only had my copy of the original 1954 Pevsner, which would have spurned an example of seaside moderne, not James Bettley’s huge and revised 2007 edition which tells me that it was designed by Howis and Belcham (they specialised in cinema design) in 1937:-

The Lovelace Courtyard

We had a small event at lunchtime today to unveil a plaque in the Lovelace Courtyard, designed by Gary Breeze:-

It celebrates the gift which made possible the design and planting in the space in between Burlington House and Burlington Gardens which used to be known as Nun’s Walk (the ghost of the nun is apparently no longer seen). It’s a very simple design by the Belgian designer Peter Wirtz: cobbles and grass and a semi-circular path; but so satisfying as seen from the Weston bridge, a small bit of green space in the heart of the city:-

Leigh-on-Sea (2)

As a footnote to my entry on Leigh-on-Sea, I was putting away my copy of Norman Scarfe’s 1968 Shell Guide to Essex and spotted my copy of Ken Worpole’s Essex Journey. It reminded me that John Fowles was a native of Leigh-on-Sea – ‘a single narrow street, with salty, muddy houses, still retaining snugly the character of fishing and naiveté’; and so too was Simon Schama, who opens Landscape and Memory with a recollection of ‘the low gull-swept estuary, the marriage bed of of salt and fresh water, stretching as far as I could see from my northern Essex bank, toward a thin black horizon on the other side’. So, too, is John Wonnacott, whose house overlooks the beach at Chalkwell and some of whose greatest paintings are not his portraits, but views of the Thames Estuary and Essex mud flats.

Leigh-on-Sea (1)

Romilly wanted to see the sea, so we took the train from Limehouse (change at Barking) to Leigh-on-Sea, what remains of a small fishing village on the western outskirts of Southend. It’s a place of pubs and boats and views across the water to Sheerness:-

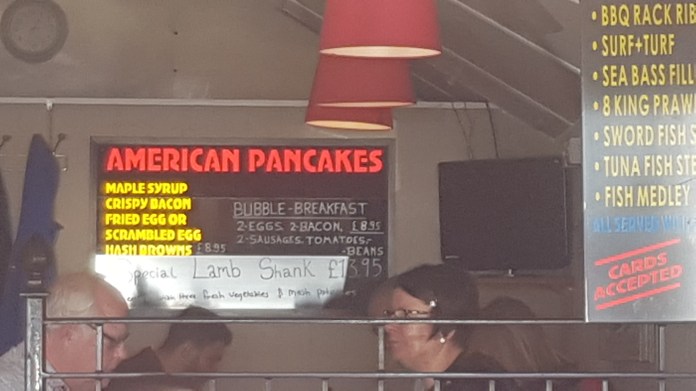

We walked along the seafront, through the more genteel Chalkwell, to Westcliff-on-Sea, with its cafés fronting onto the Esplanade:-

Southend has a funfair:-

The longest pier in the world:-

And Royal Terrace, built in the 1790s as part of the New Town and so called after Queen Caroline’s visit in 1803:-

How pleased we were to make it to Southend Station:-

Stephen Cox (2)

Last night, I went to a very beautiful exhibition by Stephen Cox RA in an antiquities gallery, Kallos, in Davies Street, in which he intermingles his own work in porphyry and marble with comparable antiquities.

It reminded me that years ago he asked me to write a short introduction to his work which, as things turned out, was never published. I checked to see if I still had it. I do and reproduce it below:-

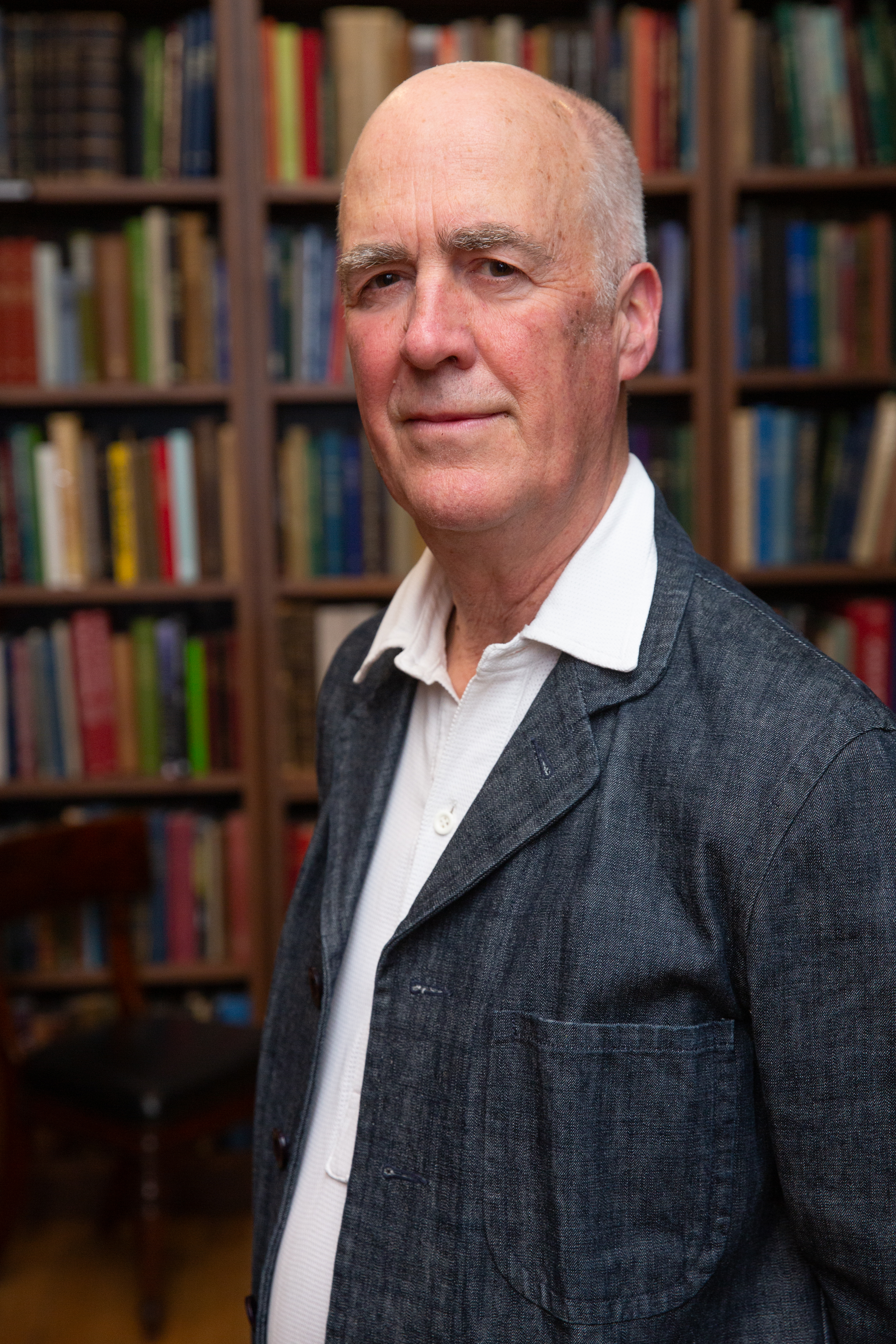

I must have first met Stephen Cox in 1994, around the time that I was appointed Director of the National Portrait Gallery, because I remember having an animated conversation with him in a restaurant in Albemarle Street about the nature and meaning of portraiture and sculpture — how far the convention retained its validity in the twentieth century, to what extent its conventions could be stretched, and whether or not it was possible to represent someone through their foot. I disagreed. More recently, I have several times been invited to attend — I should say, to witness — the opening or unveiling of new work. Each has been differently memorable because of the quality of the work itself: its classicism; its curious combination of being serene and mute and, at the same time, transcendent, intensely articulate in the ways by which it refers to the spiritual meaning of its material — marble, pietra serena, alabaster and sometimes simply raw stone. Each work has also been influenced by the choice of setting, which has invariably been a part of the experience.

Most recently, we visited the two exhibitions held near his house on the borders of Shropshire and Herefordhire: one in the new museum attached to Hereford Cathedral; the other at the Meadow Gallery in a field by the river at Burford outside Tenbury Wells, not far from his house on Clee Hill.

Slightly surreally, we walked round and round the circuit of paths, like a miniature eighteenth-century labyrinth, admiring Stephen’s larger-scale work. I retain photographs of him standing craggily beside his own rockwork and remember that Stephen Bann was there as well — not surprisingly as an interpreter of Stephen Cox’s work and someone who is enthusiastic, too, about the work of Ian Hamilton Finlay, who has, more systematically than Cox, explored the relationship between art and the garden in the Pentland hills south of Edinburgh. In Shropshire, Cox had created a small Stonehenge, very simple, out of beautiful, quite slender, nearly vertical shafts of stone. Unlike the real Stonehenge, this one could walk through and appreciate the quality of the geometry, the subtle distinctions in the shape and character of the shafts of stone.

Elsewhere in the circuit was a tomb, reminiscent of the Rothschild travertine tomb now in the grounds of Waddesdon; a stone seat; an arch into the garden; and carvings which reflect the amount of time he spends in south India. They are representative of Stephen’s work: half-oriental; half-classical; with a powerful use of the material qualities of stone and of memory, which gives his work its elegiac quality.

Renzo Piano Hon. RA

There are two things that I will particularly remember about Renzo Piano in conversation with Razia Iqbal last night: one was the sense of a tall, incredibly well preserved architect with a passionate interest in the craft of building (his father ran a Genoese construction firm) reflecting intermittently on the history of architecture – the democratic forces which led to the construction of the piazza which occupied helf the public space of the Centre Pompidou and the origins of the piazza in the idea of civitas; the other was the incredible pleasure with which he greeted the award of his diploma, more than ten years after he was made an Hon. RA.

Paul Nash

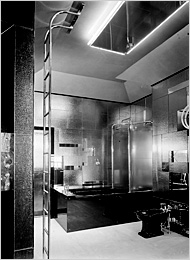

I had no idea that Edward James employed Paul Nash to design the bathroom for his house in Wimpole Street after his marriage to Tilly Losch. The floor- to-ceiling ladder was to help her exercise and the room was lined with purple glass to match her ice blue eyes. Quite something (the photograph is by Dell and Wainwright):-

Stepney City Farm (2)

I am frequently thankful for Stepney City Farm, not just for its Saturday farmers’ market bringing coxes into central London, but for its greenness, so close to the city and the construction site for Crossrail, both of which can be seen beyond the goats:-

You must be logged in to post a comment.