I went to an event this afternoon at the Prince’s Drawing School at which the Prince of Wales announced its change of name to the Royal Drawing School. I found it an unexpectedly impressive event. First, because of the quality of work by former students on display. Second, because of the recognition that a personal project of the Prince to support the teaching of drawing is now being converted into a long-term and permanent fixture of art teaching. And third, because it is now no longer a fringe experiment, but a mature project with obvious benefits and broad support.

Monthly Archives: November 2014

St. George’s, Hanover Square

A church of great dignity and parish church to Vogue House, St. George’s, Hanover Square is both architecturally strong and oddly unobtrusive, except in eighteenth-century views of the street. It’s one of the churches built under the New Churches in London and Westminster Act of 1710, begun in 1721, opened in 1724, and intended as much to enhance the authority of the monarch as of God (the portico was originally planned to accommodate a statue of George I). It was the church where Handel worshipped and he is said to have advised on its organ.

Maria Björnson

There was much discussion last night about the militant perfectionism of Maria Björnson, the great opera designer who died in the bath in her house on Hammersmith Mall on Friday 13th. December, 2002, aged 53. We got to know her on holiday in a villa near a racing track north of Florence in (I think) 1982, when she was still poor and obsessive, living in a basement flat with her mother off the Brompton Road (her mother used to do the research for her designs in the V&A library). I remember the moment when she asked whether it was sensible to take on working on a musical based in the Opéra in Paris. I advised against, because she wanted to remain faithful to what she regarded as the high art of theatre and opera and thought that she would be ostracised for designing a musical. She ignored the advice and took on the design of Phantom of the Opera which made her belatedly rich. Her obituary implies that she was shy and neurotic, but I remember her as magnificent, funny and confident (if a bit neurotic), and a genius as a designer.

The Italian Embassy

On Friday I went to a party at the Italian Embassy on Grosvenor Square. I was asked if I knew its history. I didn’t. Then, serendipitously, in leafing through the latest issue of the RA Magazine, I discovered that the Friends are going on a tour of it and, also, that there is a chapter on it in James Stourton’s Great Houses of London. The style of the house is Italianate Victorian, as required by the Grosvenor Estate, but its character is due to the fact that it was redecorated by Gerald Wellesley after Italy had been granted a 200-year lease in 1931. Wellesley, after serving as a diplomat in Rome, where he filled ‘sacks with shining porphyry, verde antico, giallo antico, and so on’, was apprenticed to Goodhart-Rendel after the first world war. John Betjeman maliciously said that he was the only architect to have a style named after him (‘jerry-built’), but the Embassy is an accomplished and appropriately opulent exercise in 30s classicism, informed by Wellesley’s taste for collecting.

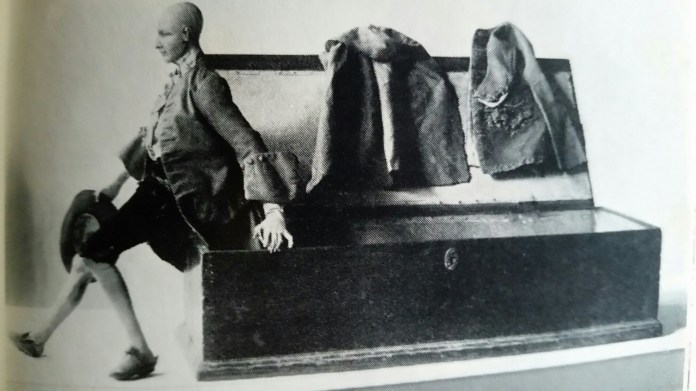

Marjorie Quennell

Yesterday was my least favourite day of the year when, as an annual ritual, I try to tidy my study. But there are occasional rewards, including this year the re-emergence of a small book which my brother kindly gave me – I think for Christmas – entitled London Craftsman: A Guide to Museums having Relics of Old Trades, published in 1939 by London Transport priced at 6d. Marjorie Quennell was co-author with her husband Charles of the four-volume A History of Everyday Things which pioneered the study of ordinary domestic objects and, in 1935, the year of her husband’s death, she was appointed as the first curator of the Geffrye Museum (she lived on after the war until 1972). Her book was advertised as ‘a tour of London’ in which ‘She shows you where to see the things that London craftsmen used to make, and the tools with which they made them’. The museums include the London Museum, then housed in Lancaster House (and had a 6d. entrance fee mid-week), the Horniman Museum, which had a section of bygones, and the Bethnal Green Museum, which was described as ‘very popular’ and had a special display of Spitalfields silk.

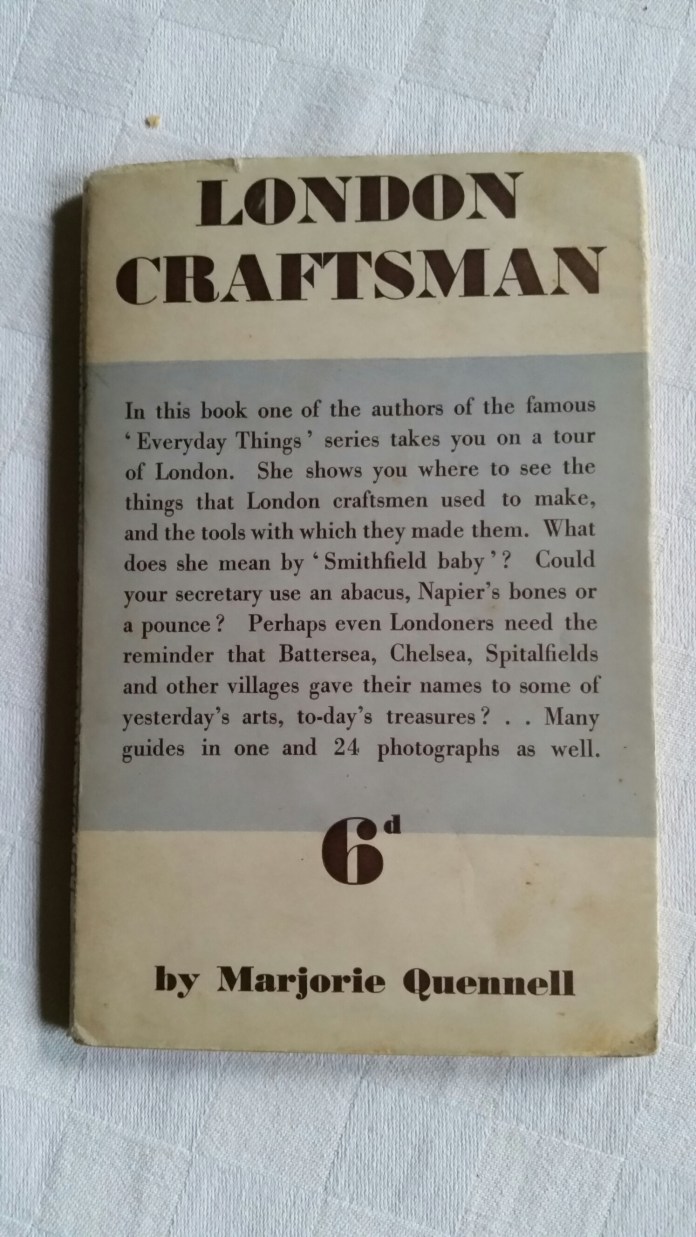

Described as a ‘Model of a Mahogany Staircase’ in the V&A:

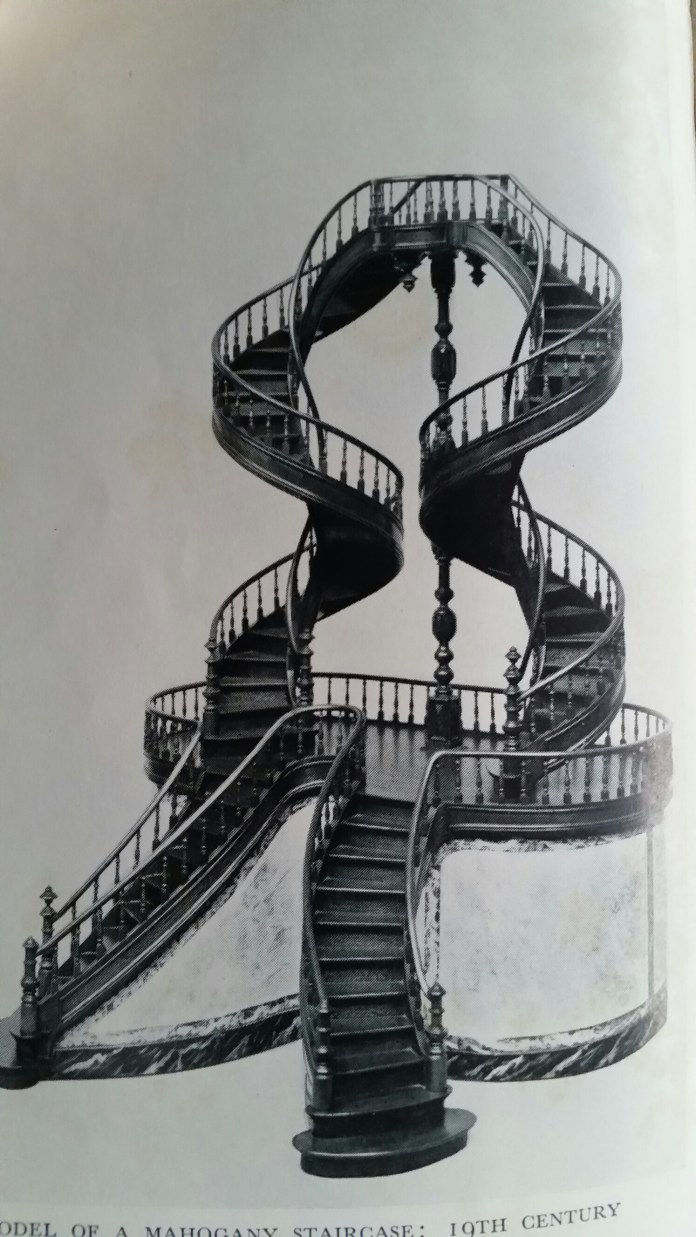

Roubiliac’s lay figure in the London Museum:

The Unshrinkables

I sadly missed the parade of the so-called Unshrinkables in the courtyard on Monday. They were a group of volunteers who, in an outbreak of patriotism, joined a volunteer force in August 1914, many of them members of the Chelsea Arts Club, who paraded in its garden wearing white woolly jerseys (‘unshrinkable’) and carrying broomsticks. In October 1914, they moved their parades to the courtyard of the Royal Academy, where they were also given the use of some of the galleries and the refreshment room as a mess. At the weekend they went to Taplow Court, the home of Lord Desborough, to practice digging trenches. Today, I was presented with a replica of their badge, known as ‘the duck and skewer’, designed by Solomon Solomon RA:

Sir Steven Runciman

In travelling back from Istanbul, I was reminded of Steven Runciman, the great historian of the Crusades, who spent the second world war as Professor of Byzantine Art at Istanbul University, after serving as press attaché in Sofia on the recommendation of his pupil Guy Burgess. He used to say that to be an effective historian of the Crusades it was necessary to have mastered seventeen languages, which he had, having learned Greek and Latin by the age of six.

Mustafa Pasha Mansion

Our final evening in Istanbul was spent on the banks of the Bosphorus in the Mustafa Pasha mansion, built for a coffee magnate in the late eighteenth century and now owned by the Çetindoğans, major collectors who are in the process of building a museum by Zaha Hadid. I particularly admired their private Turkish bath:

And the place setting which included my initial in bread:

The Ottoman Empire

In the intervals of visiting Istanbul, I have been reading Norman Stone’s very readable, succinct short history of Turkey, since he’s the only person I know who makes the movement of eastern European politics intelligible. I’m struck by his comments on the Ottomans, that most people in western Europe inherit a prejudice that the Ottoman Empire was incompetent and effete, if not murderous, as it perhaps became towards the end, but that in its heyday it was immensely successful, stretching in a great arc from the Balkans to Beirut and round to Morocco in the west. He does not say, but it is obvious, that there is something inevitably sclerotic in these great Empires which rely on light rule and high taxation, although he does gently point out that the Ottoman record compares well with that of the British Empire ‘which – though a viceroy in 1904 thought that it would go on ‘for ever’ – lasted less than a century’.

Old Istanbul

Although I have very much appreciated the chance to see the major sights of Istanbul, I have also enjoyed the occasional glimpses of an older city, less obviously westernised, surviving from Ottoman times in the backstreets and doorways, in the grand façades of Galata and most of all in the streets down below the Grand Bazaar:

You must be logged in to post a comment.