As we build up to the opening of our Allen Jones exhibition in Burlington Gardens next week, a lone statue has appeared in front of our building. It looks impressive, hydra-headed, as if it doesn’t know whether to belong to Bond Street or Regent Street. We have been discussing with a number of local bodies, including Westminster City Council and the New West End Company, how to improve the look-and-feel of the neighbourhood. One public sculpture shows what a difference a well chosen intervention can make:

Monthly Archives: November 2014

Regent House

On the occasions when I travel to Oxford Circus (it’s marginally quicker), my eye is often caught by the mosaics above the Apple Store on Regent Street: PARIS NEW YORK ST. PETERSBURG BERLIN. It gives me a momentary twinge of disappointment that I’m not standing on a platform at Waterloo or the Gare du Nord. I have often wondered what the building used to be. The answer is not that it was the headquarters of Thomas Cook, but instead advertised the work of Dr. Antonio Salviati, a Venetian mosaicist who restored the mosaics of St. Mark’s and went on to work on the Albert Memorial and St. Paul’s. The cities listed above the windows were the cities where the Compagni Salviati had shops:

Mr. Turner (2)

I have been cogitating about the comment from Edward Chaney that Mr. Turner is too focussed on issues of class. But there surely was, and is, a class aspect to the fact that Turner was born the son of a Covent Garden barber, retained a working class accent throughout his life, but owed much of his early success to the support of major collectors, including Richard Colt Hoare, the antiquary and owner of Stourhead, Edward Lascelles, heir to Harewood, the Earl of Yarborough of Brocklesby, as well as William Beckford and John Julius Angerstein, less aristocratic collectors. I thought that two of the convincing scenes in the film were, first, the way that Lord Egremont supported Turner at Petworth and, second, the way that Turner was supported at the RA over Constable, who was the same generation, but slightly more middle class. It demonstrates the way that talent beat class.

St. James’s, Piccadilly

Whilst waiting for Hatchard’s to open one day last week, I wandered in to St. James’s, Piccadilly, which I pass so often, but scarcely go into except for memorial services. I know from Lucy Winkett, its wonderful Rector (and chaplain to the RA), that the PCC are grappling, and have been for a long time, how to restore it:

Louis Vuitton Bookstore

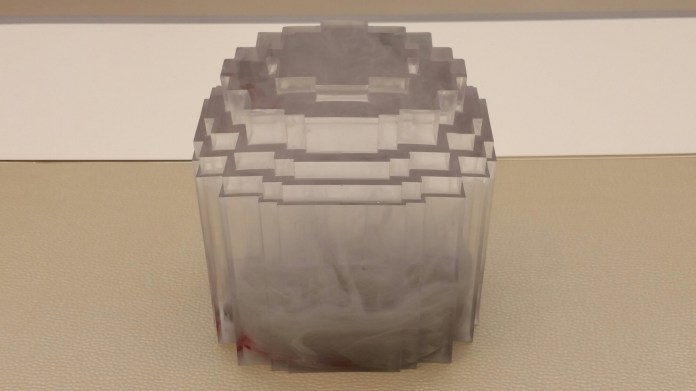

Very few people know that Louis Vuitton on Bond Street harbours a well-stocked art bookshop on its first floor, which has vintage editions and small-scale works of art, including a beautiful piece by Alison Wilding inspired by a radio play about the way that scientists experimented on creating a nuclear explosion in a squash court in Chicago.

This is the shop:

And this is the piece by Alison Wilding:

Second Home

I have just been to an intriguing event in Hanbury Street in Spitalfields, next door to Atlantis Paper and just off Brick Lane, where Rohan Silva, a young entrepreneur who used to work in 10, Downing Street has established a casual, serviced work space for hi-tech and digital start-up companies. The architecture is industrial chic – Silicon Valley meets Brick Lane – with balloon windows onto the street, designed by Selgas Cano, a young Spanish practice which specialises in new work spaces (their own office is incarcerated in the woods). I was told that key to the success of the project is proximity to good food. Sadly, I missed the speech by the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

H.W. Pickersgill

One of the artists who has a walk-on part on Mr. Turner is Henry William Pickersgill, a dutiful and diligent portrait painter, who was adopted by a Spitalfields weaver, trained at the RA Schools, was respected by Constable, and had ‘a clever wife, who manages all matters for him’. Admired for his sober likenesses, much employed by Oxbridge colleges, he painted the Victorian meritocracy, was an RA for fifty years, ended up as its librarian, and is now pretty wholly forgotten.

Mr. Turner (1)

We went to what felt like an artists’ screening of Mr. Turner at the Rich Mix with all the local artists out in force to assess the veracity of its depiction of a painter. What was the verdict ? Very convincing: an amazing performance by Timothy Spall conveying the arrogant, uncouth and hog-like characteristics of Turner and his visual obsession with boats and sky; a historically well-judged depiction of the politics of the RA, including Constable being rebuffed on varnishing day; admirable performances by Paul Jesson as Turner’s father and Marion Bailey as Mrs. Booth; and exceptional in the way that the film does (and does not) show Turner actually painting, much more persuasive than most depictions of painting on film (you only have to think of The Draughtsman’s Contract). My only quibbles were that his house in Harley Street looked too new, Queen Victoria never visited Somerset House, and Ruskin was not such a twerp.

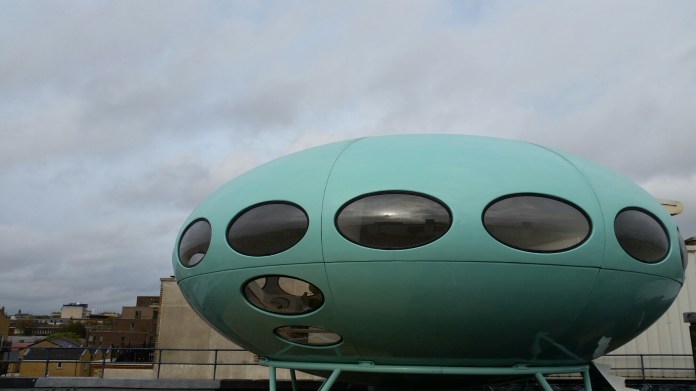

The Futuro House

We went on a little excursion this morning to see the Futuro House which looks as if it’s landed like an alien spacecraft on the roof of Matt’s Gallery next door to the Ragged School Museum on the Regent’s Canal. The first Futuro House was designed in the 1960s in Finland as a ski cabin and they were then manufactured as cheap homes. But they were so unpopular that they were subjected to drive-by shootings in the United States. This one was found ruined in South Africa and has been meticulously restored by Craig Barnes, an architect, maybe as an example of cheap manufactured homes:

C.R. Ashbee

Mention of C.R. Ashbee in connection with Trinity Green has made me want to know more about his time living and working in the east end. He read history at King’s College, Cambridge from 1883 to 1886, where he was much influenced by Edward Carpenter and the writings of Morris and Ruskin. He was then articled as a clerk in the firm of Bodley and Garner, the best of late Victorian gothicists, and lived in Toynbee Hall as a way of developing his socialist ideals. On 23 June 1888 (ie when he was only 25), he established the Guild and School of Handicraft at 34, Commercial Street on the top floor of a warehouse next to Toynbee Hall. In 1891, the Guild acquired workshops away from the densely built and poorest part of Whitechapel in Essex House at 401, Mile End Road, a fine brick eighteenth-century mansion with panelled rooms, a bachelor flat for Ashbee himself when he was not in Chelsea, and a garden with ‘a couple of good box trees, three or four pears and crabs, some cherry trees, laburnums and ash, and a number of vines’. It was on the site of Onyx House opposite Mile End station. There the Guild grew from a tiny operation to employing up to 40 people making furniture and other aesthetic products, mostly to Ashbee’s design.

You must be logged in to post a comment.