We had an event tonight to celebrate the Rolex Mentor and Protégé programme which has been running since 2002, whereby extremely well-known figures in the arts world (this year including Philip Glass and David Chipperfield) take on a young and rising star in their field as a protégé. It sounds as if it could be a corporate gimmick, but they have been doing it over a long period of time and have invested not just large sums of money, but long-term moral and organisational support. What I found particularly interesting is that Rolex is run not as a profit-making corporation, but as a private trust (it was originally established in London in 1905), investing its profits in community good. We don’t hear enough about these different corporate models and how they operate.

Monthly Archives: September 2017

Richard Llewelyn Davies

I don’t think I had ever previously registered that the north-east extension to the Tate was designed by Richard Llewelyn Davies, the well-known hospital planner, analytical technocrat, destroyer of the Euston Arch and designer of Milton Keynes, who is said never to have been to school before studying mechanical sciences at Cambridge. In fact, I have discovered that he was first involved in drawing up plans in 1964, when he proposed demolishing the original classical portico and constructing a new building between the Tate and the river. This Brave New World scheme was rejected following its public exhibition in 1968. His new galleries in the so-called North-East Quadrant (Plan B) eventually opened in 1979 and, following his death in 1981, were described by the New York Times as ‘bleak and warehouselike, but Lord Llewelyn-Davies regarded it as appropriate to the modern paintings it was intended to display’. I actually prefer them, with their high ceilings and robust anonymity, to the lower ceilinged galleries downstairs.

Rachel Whiteread

It is always very hard to appreciate the work of an artist at a crowded private view, let alone an artist whose work is so monumental and expressively mute as Rachel Whiteread. So, all I can say is what a good and brave thing it is that Tate Britain has cleared out the whole of Richard Llewelyn Davies’s 1979 north-east extension in order to be able to see an enormous range of Whiteread’s work in an open, clear space:-

Design Museum

We had a day of intense discussion in the Design Museum, hearing what they felt had gone well (and less well) in their planning and opening arrangements. It was very helpful to hear from others as we approach our own big opening next year on how to manage a huge organisational change: the biggest thing I learned is that not everything is predictable; and that Rowley Leigh has taken over the catering:-

Soane and Freemasonry

I should maybe have said that what prompted my interest as to whether or not Hawksmoor was a freemason was a reference to the fact which I wasn’t completely persuaded was true (but am now) in an excellent short essay by James Campbell, ‘Sir John Soane and the Freemasons’, in a forthcoming publication Soane’s Ark: Building with Symbols, ed. F. Saumarez Smith, which is being published by Factum Arte alongside an exhibition at the Soane Museum which reconstructs Soane’s great Ark of the Masonic Covenant, destroyed by fire along with the rest of the then Mason’s Hall in 1883. Opens on 11 October.

Hawksmoor and Freemasonry

I hav been trying to find out whether or not Hawksmoor was a freemason, as he is generally assumed to be following Peter Ackroyd’s very convincing, but entirely fictitious invention of him as a necromancer. The answer, as I have discovered in a very informative Exeter University PhD. thesis by Richard Berman on The Architects of English Freemasonry, 1720-1740, is that he is listed as such in the Grand Lodge Minutes under the name ‘Hawkesmoor’; and that his future son-in-law, Nathaniel Blackerby, with whom he went on a trip round southern England in the early 1730s and who was to write his obituary in Reed’s Weekly Journal, was extremely active as a freemason, serving as Grand Warden in 1727 and Deputy Grand Master the following year, alongside his work as Treasurer to the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches. But as James Campbell, the expert on this topic, points out, Hawksmoor was only initiated in 1730 at the Oxford Arms in Ludgate Street, towards the end of his career, so it is implausible pace Ackroyd et. al. that it had any influence on his architectural ideas.

Christopher Wren FRS (2)

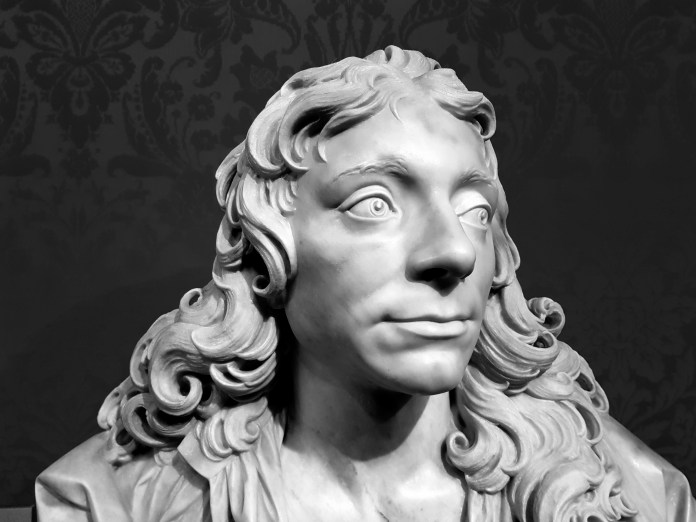

I have been pondering how it was that Edward Pearce, a highly experienced mason-contractor, who worked on a range of different building contracts as well as St. Paul’s should have been responsible for the virtuoso head of Wren who was his employer. Pearce did undertake work as a sculptor, including a bust of Oliver Cromwell in the Museum of London, which is signed and dated 1672, and two busts commissioned respectively by the Painter-Stainers Company and Royal College of Physicians. The bust of Wren was presented to the University of Oxford by Wren’s son, also called Christopher, who was a great collector of manuscripts and information about his father, as well as working in the Office of Works. So, it has an impeccable provenance. But Nick Penny in his catalogue of the sculpture in the Ashmolean speculates that it may be a copy by Pearce of a lost original by Coysevox, presumably undertaken on Wren’s brief trip to Paris. Doesn’t seem likely to be unrecorded.

Woman’s Hour Craft Prize

I missed the opening of the Woman’s Hour Craft Prize on Tuesday, so took the first opportunity to see the full range of the work on display, not just Romilly’s, having listened last night to all twelve of the Today programme interviews online (it’s a good way to get a feel what can be legitimately shown under the umbrella of craft, including bicycles made by a jeweller and work which autodestructs).

First, you have to find it. It’s on the first floor of the Henry Cole Wing, which you reach by going through the new Sackler Centre shop and up the stairs by the Information Desk.

Peter Marigold’s Bleed series is artisan/craft/handmade/conceptual all at once:-

Then the bicycle, a beautiful and immaculate piece of hand-built engineering:-

I’m keen on Celia Pym’s work repairing jerseys as we’re plagued by moths and I like the way the quality of repair invests the piece of clothing with a new life and meaning:-

I had never seen one of Phoebe Cummings’s works, which are astonishingly virtuoso in their use of raw clay. You feel their magnificent, but terrifying temporality:-

Romilly’s is towards the back and is maybe more reticent because smaller scale. She has moved into boxes, still using found archaeological objects which she buys on ebay, including (my favourite) Winter Boxtree, made out of an Anglo-Saxon ring:-

And Tudor Glass with Coral Reef:-

It’s hard to photograph the full ensemble:-

I had seen Laura Youngson Coll’s work in Jerwood Open, but was more impressed by its amazing delicacy and refinement here, made out of vellum and fish skin:-

On the other side is work by Andrea Walsh – very refined, highly abstract minimalism:-

I don’t envy the task of the judges who have to pick a single winner from so much category diversity.

David Tindle RA

In amongst the strong, if somewhat conservative, collection of modern British art in the Ashmolean is a very strong (inscribed on the back 1955, although undated on the label) painting by David Tindle, which shows how close his early work was in style and character to that of John Minton and Lucian Freud (his first solo show was at the Piccadilly Gallery in 1954). I also had not realised that he had been Ruskin Master, as well as an RA since 1979:-

Christopher Wren FRS (1)

I was wandering round the Ashmolean when I came upon Edward Pearce’s bust of Christopher Wren, which I had forgotten was here – a bust of such extraordinary liveliness and luminous intelligence. Of course, one is discouraged from reading character out of the way someone is represented artistically, but it is hard not to from Pearce’s extraordinarily effective depiction of Wren in the early 1670s, when he was at the height of his powers, embarking on the long journey of designing and building St. Paul’s, using Edward Pearce, its sculptor, as one of his draughtsman, employed to do drawings (‘Modells’) for the portico and dome:-

You must be logged in to post a comment.