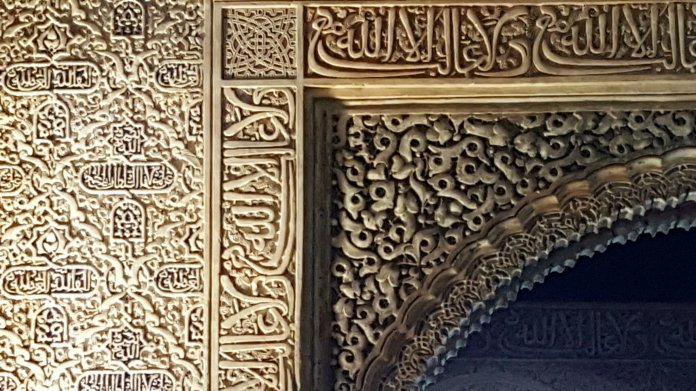

We made it to the Alhambra, not without difficulty, passing through many circles of tourist hell, and quite unprepared, in spite of having read plenty of guidebooks in preparation, for the full glory of the Moorish decoration, the way the light plays on it, the passage through courtyards, and the extraordinary volcanic energy of the ornament.

First of the major sights along the Calle Real is the Palacio de Carlos V, a statement of robust classicism following the Conquest of the Moors, designed by Pedro Machuca, a pupil of Michelangelo:-

Inside is a noble circular courtyard:-

We were not detained by the Alcazaba, the fortress at the end of the hill overlooking Granada:-

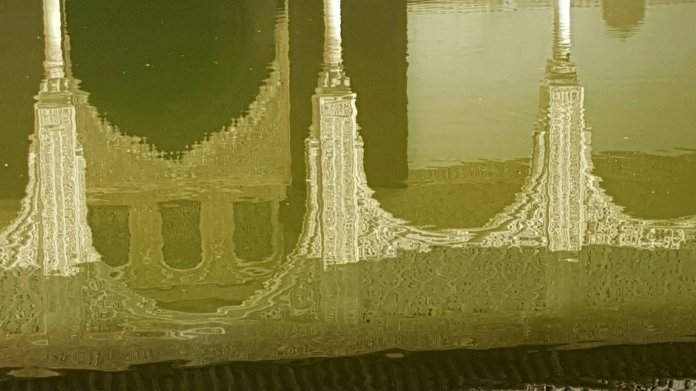

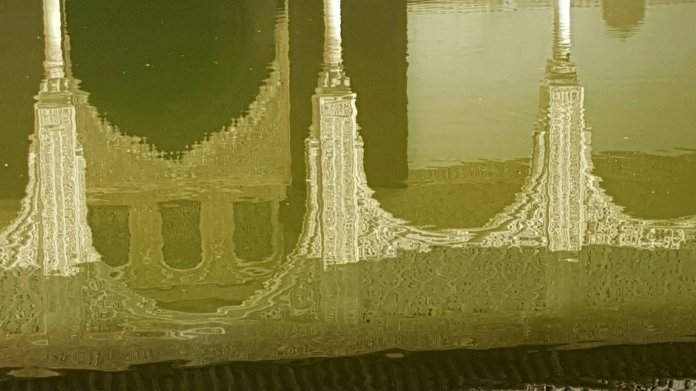

Instead, we took the ramp straight down into the Patio de los Arrayanes – the Court of the Myrtles:-

Everywhere, there was very beautiful, rampant, ornamental decoration:-

At the north end is the Sala de la Barca:-

Then through into the Patio de los Leones:-

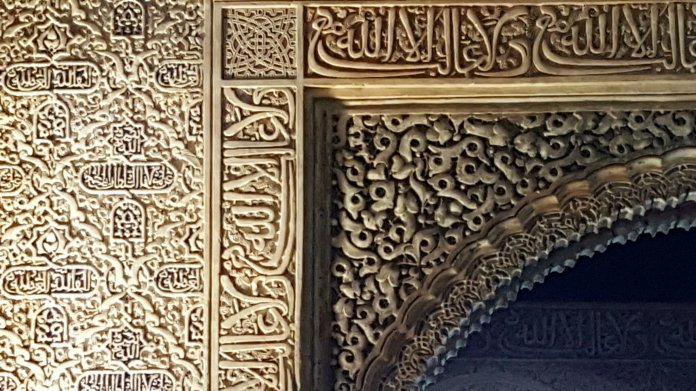

I will end the morning tour with the wild decoration of the Sala de los Abencerrajes:-

You must be logged in to post a comment.