By special request, I am posting a picture of a Piedmontese milk machine in the high street of Bagnolo. I thought there were two, but it turns out that the other one offers a choice of still or sparkling mineral water. It’s flanked by a second machine which provides fresh cheese and a third condoms. It’s symbolic of Piedmontese food culture that one can get fresh, unpasteurised milk, twenty four hours a day, out of a blue teat in a bring your own, recycled bottle:-

Monthly Archives: August 2017

The Revenge of Analog

I have been reading The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter, a book published last year by a Canadian writer, David Sax, which analyses the ways in which, in a number of industries, new disruptive digital technologies which appear to revolutionise an industry have frequently been superceded or supplemented by a niche reinvention of the older analogue technology, as in the rediscovery of the merits of vinyl, the making and marketing of Moleskine notebooks, a relatively recent invention (they were only established in 1997), the revival of specialist print magazines (Cereal is given the example, alongside the growth in circulation of the Economist), the opening of new local bookshops, and Shinola, the new manufacturing company based in Detroit. The narrative in each of the chapters is essentially the same: the superficial allure of new digital technology, followed by the discovery that new systems of digital working cannot altogether replace the virtues and benefits of empathy, emotion and human interaction. It feels like an appropriate book to be reading in the land of Slow Food.

Bagnolo (2)

After two days of thunderstorms, it’s beautifully green and clear, so we have stayed in the vicinity of Bagnolo with its Cooperativa Agricola and coin-in-the-slot milk machine:-

Guarino Guarini

I have been trying to get to grips with the history of Piedmontese architecture as background to visiting the buildings. Key to understanding it is obviously the career of Guarini, trained as a Theatine monk and the most intellectual of architects, equalled perhaps only by Wren, who was his nearly exact contemporary (Guarini was born in 1624, Wren in 1632; both visited and were influenced by Parisian architecture in the 1660s). Born in Modena, Guarini was ordained in 1648 and remained there until 1657, when he left to travel, visiting Prague, Lisbon and Messina, where he was a Lecturer in Mathematics. In 1662, he arrived in Paris to design the Theatine church of Sainte-Anne-la-Royale. Reading about him in Richard Pommer’s history of Eighteenth-Century Architecture in Piedmont: The Open Structures of Juvarra, Alfieri, and Vittone (still, so far, as I am aware, the best account), he was much influenced by the intellectual atmosphere of Paris at the time, particularly the new found admiration for gothic, as expressed by Claude Perrault: ‘in contrast to the taste of Greek architects, who could find no beauty in a structure that didn’t look solid, Gothic architects loved the appearance of the miraculous, and built extremely long and slender columns to sustain great vaults, which actually rest on brackets suspended in air’. In 1666, he arrived in Turin to design the Theatine church of San Lorenzo, which Pommer describes as ‘a great work of hallucinatory engineering’. Not long afterwards, he began work on the Santissima Sindone. A decade later, in 1679, he was commissioned by Prince Emmanuel Philbert, a deaf mute, to design the Palazzo Carignano on the site of the old royal stables. Again, Pommer is helpful is explaining the intellectual and dynastic background to the conditions of buildiing: ‘The urban scene was left plain and monotonous, a vast series of tan barracks constructed by an autocratic policy that demanded the rapid enlargement of Turin with uniform rows of palace façades fencing in long, straight streets…But against this reticent background, a few churches, palaces and country residences were set off by their showy grandeur, overrichness, or flagrant ‘bizzarria’. In many ways, the Dukes of Savoy were militant, austere, and even puritanical; in architecture they often sported a taste for the strange or flashy’.

Turin (2)

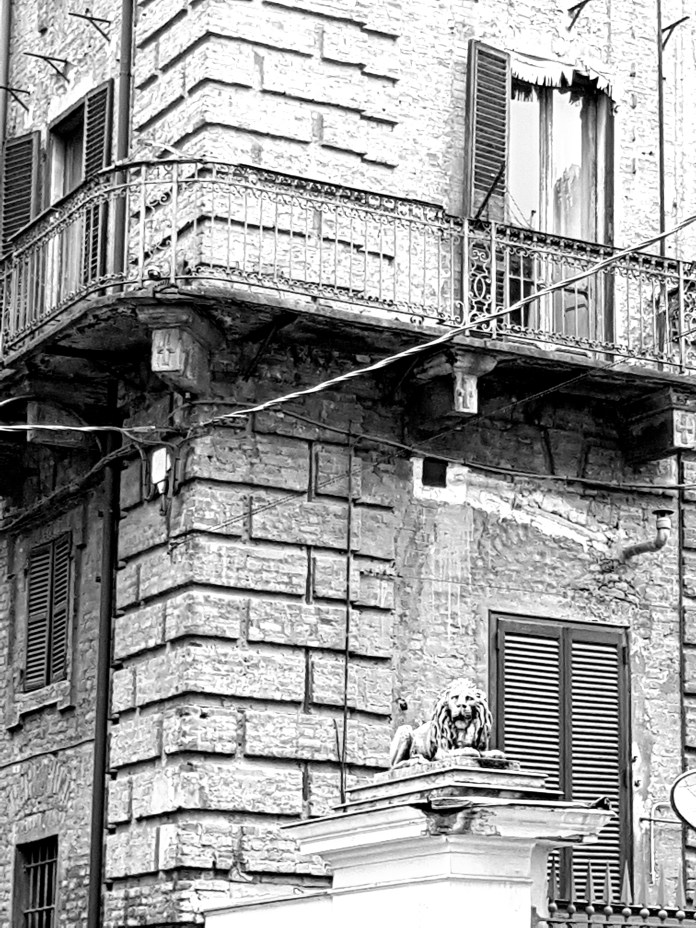

After coffee, we went to see the Palazzo Carignano, which we’ve done plenty of times before, with its curving brick façade designed by Guarini in 1679 with liquid window surrounds like curtains and an internal courtyard of elaborate geometric brickwork which leads to the Museo del Risorgimento:-

En route to lunch, we stopped to admire the façade of the Basilica Corpus Domini, with its statuary by Bernardo Falconi:-

After lunch, we wandered through the Quadrilatero Romano. Admired another, more recent work by Aimaro d’Isola, the Hotel S. Stefano:-

Found a palazzo for sale in the Via della Basilica:-

Good stonework detailing and bull’s heads in the Via Milano, the street leading out of the Porta Palazzo market:-

By now, we needed another cup of coffee, but Al Bicerin, our destination, was closed.

Turin (1)

We had a long morning’s architectural touring in Turin, starting in the neoclassical stateliness of the Pizza Vittoria Veneto, where one of the old pharmacies caught our eye:-

Then to one of Aimaro d’Isola’s canonical early works, a street front which is definitely mannered for 1952, with elaborate, slightly gothic, brick detailing, offset by Luserna stone (the lamp standards don’t belong):-

It’s nearly opposite the Mole Antonelliana, a surreal building for a synagogue:-

There were two good brick buildings on either side of the Via Giuseppe Verdi. One turned out to be the Palazzo dell’Universita, designed in 1712, but neoclassical in character:-

We never did discover what the one opposite is:-

We stopped for an espresso at the Café Mulassano, a perfect art nouveau interior by Giulio Casanova:-

Basilica di Superga

We were the only visitors to the Basilica di Superga first thing in the morning right at the top of the highest hill east of Turin. It was, as we remembered it, grand and forbidding and rather gloomy, with a too large portico and an air of German rather than Italian baroque:-

Cherasco

We loved Cherasco, a well planned, small town on a strict grid with triumphal arches at either end of the main street and a wealth of good architecture:-

The wonderful Sanctuario Madonna del Popolo (1693):-

And S. Pietro:-

Bra

We went to Bra, the home of the Slow Food movement. But we failed to get into Boccodivino, the restaurant which everyone recommends, so had to console ourselves with baroque churches.

First, S. Andrea, a church thought to have been designed by Bernini and executed by Guarino Guarini in 1672, but these attribitions are disputed by Richard Pommer who thinks they are the result of ‘too much campanilismo‘:-

Then up the street to S. Chiara, by Bernardo Vittone, much more theatrical, started in March 1742 and completed six years later:-

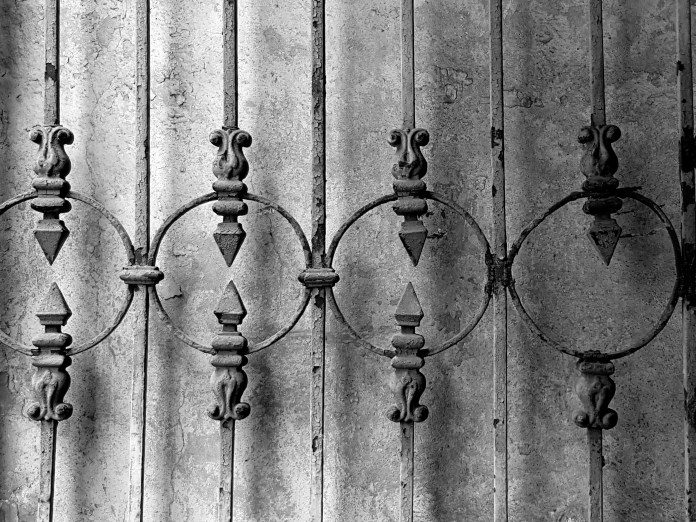

We particularly liked the extraordinarily elaborate, nearly art nouveau ironwork:-

There was much else to see in Bra. The Corso Cottolengo and Santissimo Trinità beyond:-

The art nouveau sculpture in the main square:-

The Palazzo Communale:-

And assorted courtyards, doorways and street signs along the Via Vittorio Emmanuele II:-

And assorted courtyards, doorways and street signs along the Via Vittorio Emmanuele II:-

S. Marcellino, Envie

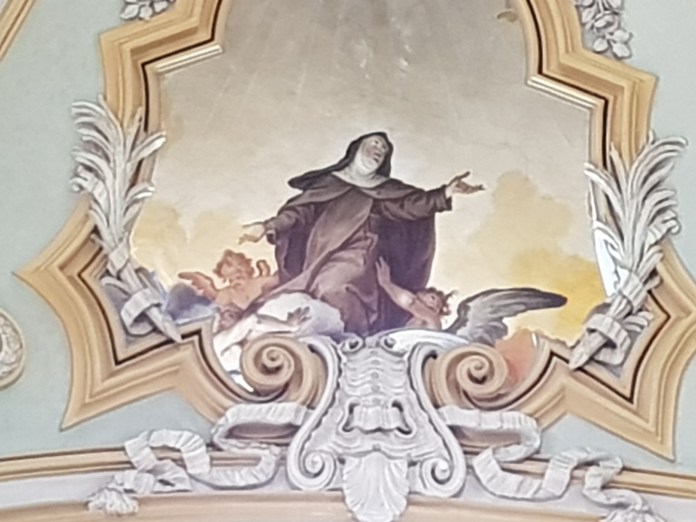

We were driving through Envie en route to Bra and stopped to admire the elaborate brickwork decoration of S. Marcellino, a church with a Romanesque tower, but much reconstructed in 1762, still baroque and with an undisturbed interior:-

You must be logged in to post a comment.