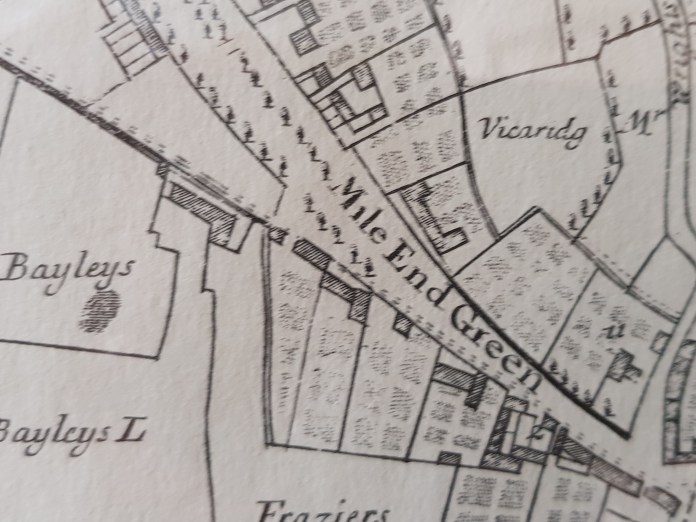

We ended the patrons’ tour of Stepney by looking at a map which was made in 1703 by Joel Gascoyne of ‘The Parish of St Dunstan Stepney alias Stebunheath Being one of the Ten Parishes in the County of Middlesex adjacent to the City of London’. What I found more fascinating than the depiction of Stepney Green (then called Mile End Green) as it was in 1703:-

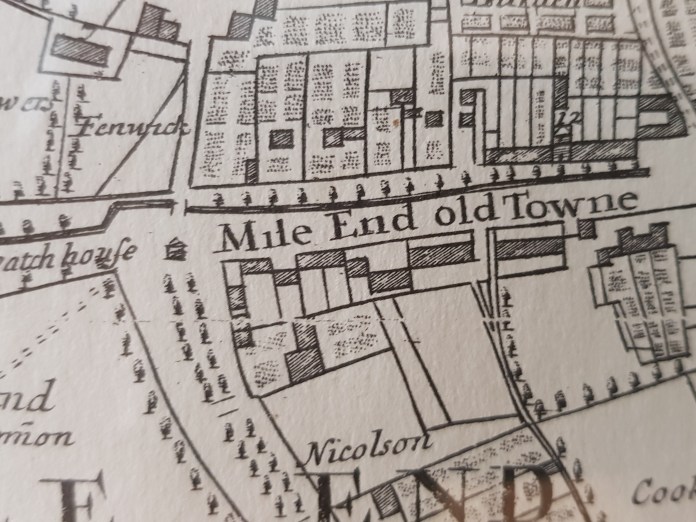

And the houses set back from the Mile End Road (Mile End old Towne)-

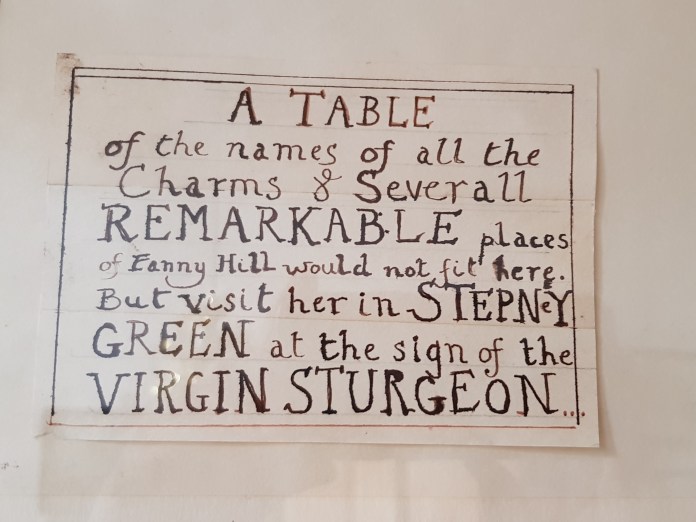

Was the inscription which had been added which implied that Stepney Green was a place of ill repute:-

You must be logged in to post a comment.